A TRIXIE SPECIAL!

At the Q. and A. session after The Shakespeare Code’s talk to the Titchfield History Society, there was one question on everybody’s lips…..

How could Titchfield – and the Earl of Southampton – have been so airbrushed from The Rise of a Genius – the BBC T.V. biography of Shakespeare?

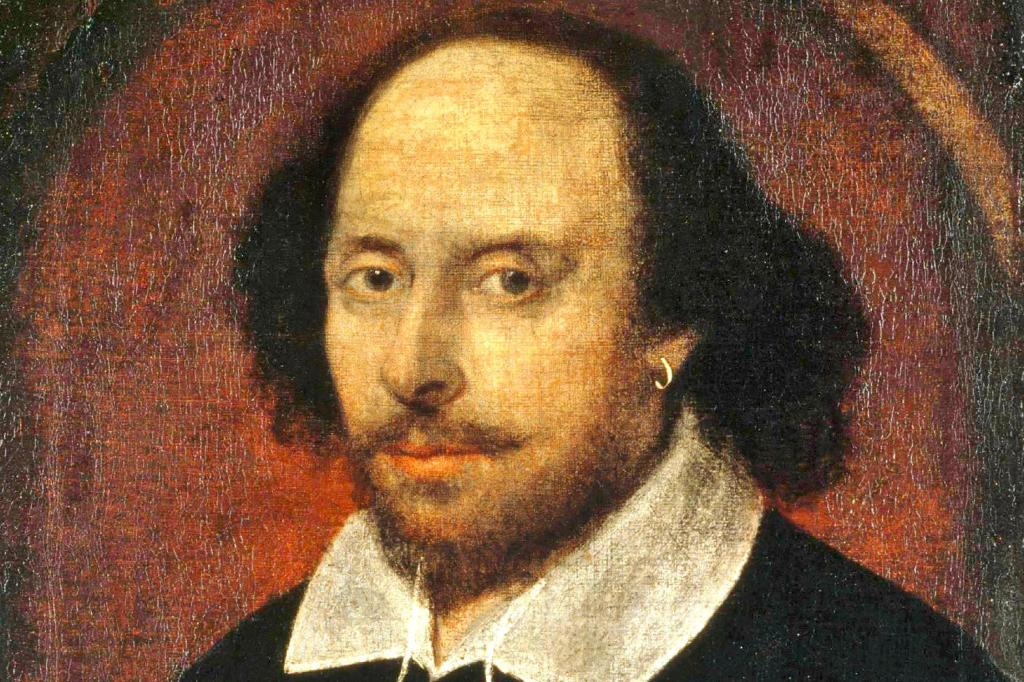

Why was there no mention of the man to whom Will had dedicated, in respectful and loving terrms, two, long, narrative poems?

Several theories were put forward…..

The first was power. Stratford-upon-Avon was in no mood to yield its supremacy in the Shakespeare story.

The Code’s Chief Agent revealed that Melvyn Bragg…..

……..had written a letter to him (at the start of the century!) which said:

‘Watch out, Stratford-upon-Avon!’.

Also there are two modern assumptions which blinded the BBC to the truth:

(1) A genius is a lone figure producing masterpieces in solitude.

What the Titchfield Theory offers is the idea of a collective genius – a group of people coming together with like aims and ambitions – one of whom, at least, is very talented……

……and one of whom, at least, is very rich!

(2) Good art will always make money.

You only have to run a theatre, as The Code’s Chief Agent has done, to realise this is simply not true. The public are reluctant to attend anything that’s new or strange – and writers producing challenging scripts needs all the financial aid they can muster.

Southampton not only supplied Shakespeare with £1,000 – he provided him with an appreciative, intelligent, educated and daring public….

….the Elizabethan…..

…….and Jacobbean…….

…….royalty and aristocracy.

But there is another factor – which we have named ‘Swift Syndrome’.

Johnathan Swift…….

…….wrote:

‘When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him’.

We have observed, in our research for this talk, this phenomenon occurring time after time.

For example….

In 1709 Nicholas Rowe sleuths out two great stories about Shakespeare….

1. He poached deer from Sir Thomas Lucy’s park.

2. Harry gave him a gift of £1,000.

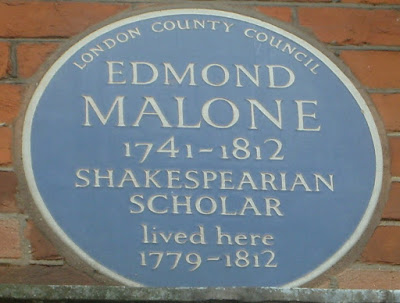

Edmond Malone – who never once visits Stratford – comes along seventy years later and rubbishes these discoveries.

Scholars then parrot what Malone said for the next 150 years!

Dover Wilson – linking literature with history – posits the theory in the 1920s and 30s that Will was a tutor to Harry at Titchfield, got involved in the Essex Rebellion and travelled to Scotland to persuade King James to invade England.

Dover Wilson’s nemesis, W.W. Greg, the editor of the Malone Society no less, describes Dover Wilson’s theories as…..

‘the careerings of a not too captive balloon in a high wind.’

Sadly, Dover Wilson, a sensitive man, takes this criticism to heart, and rescinds many of his theories.

He even follows fashion by declaring that ‘the lovely boy’ is in fact William Herbert.

This fashion comes largely from E. K. Chambers…….

…..(the first President of the Malone Society) who had originally thought ‘the lovely boy’ was Harry – but changes his mind in 1930 and names him as William Herbert, the Third Earl of Pembroke.

Many of the scholar-lemmings follow.

As late as 2010, Katharine Duncan-Jones – in her updated Arden edition of the Sonnets – writes:

‘Dover Wilson’s speculations are attractive. He suggested that the Countess of Pembroke ‘asked [Shakespeare] to meet the young lord at Wilton, on his seventeenth birthday’ and commissioned him to compose an appropriate number of pro-marriage sonnets for the occassion’. This would locate sonnets 1-17 in April 1597.’

But the Herbert Theory can be demolished in a second…..

In Sonnet 13 Will writes to the young man:

You had a father – let your son say so.

William Herbert’s father, though ill, was still alive in 1597.

Harry Southampton’s father in 1590 – the year of Harry’s seventeenth birthday – had been dead for nearly a decade!

[The Second Earl of Southampton – Photo Ross Underwood]

The Shakespeare Code sincerely hopes that it will hear no more about William Herbert as ‘the lovely boy’.

He was clearly Harry Southampton!

To return to ‘Swift Syndrome’….

The distinguished Cornish historian, A. L. Rowse….

……discovers in 1973 that the Dark Lady of the Sonnets was Amelia Bassano/Lanyer.

She fits the role to perfection – down to her musicianship, her flirtations and even the way she ‘rolls’ her eyes….

Rowse writes an article for The Times, makes a couple of unimportant technical mistakes and Stanley Wells rubbishes the whole theory on BBC radio…..

……..putting back Shakespeare Studies by at least fifty years.

Prof. Roger Prior – who believes, along with the Shakespeare Code, that Amelia was the Dark Lady and Harry the ‘lovely boy’ and that Will visited Italy in 1593 – puts Wells’s response down partly to the ‘New Criticism’ – a movement that came from America in the 1920s and 30s – which….

‘…removes the author from the text. The author’s thoughts and intentions, it is claimed, can never be known, and are in any case quite irrelevant to our understanding of his work. A Shakespeare sonnet may seem to be addressed to the Earl of Southampton, but this may be no more than a clever fictional trope…the literary work of art has nothing to do with the world…..’

This movement was inspired by an essay written by T.S. Eliot….

…..over a hundred yhears ago!

He wrote:

‘The more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the man who suffers and the mind which creates; the more perfectly will the mind digest and transmute the passions which are its material.’

The reason Eliot wrote this is that he was afraid that when people discovered how appalling he was in his private life, they would shun his poetry.

But F. R. Leavis – a Cambridge, bicycling don…..

…….was flattered by Eliot’s attention – and taken in by him – even if his wife Queenie wasn’t.

So Eliot’s beliefs swamped the whole of Academic life in Britain and America – up to Rowse’s ‘Dark Lady’ discovery in 1973.

But Stanley Wells is still everywhere….

Even the Code’s Chief Agent has been attacked by him!

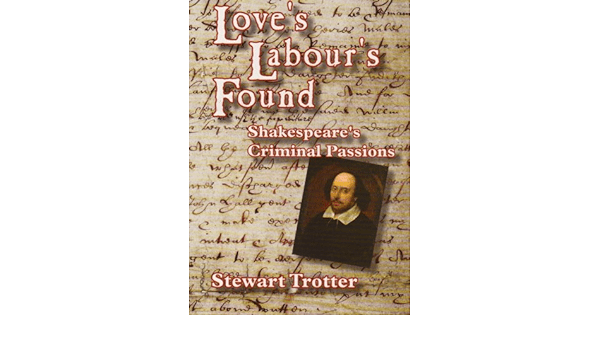

He wrote Love’s Labour’s Found in 2000…

…….and appeared in a Meridian TV documentary – developing Dover Wilson’s theory that Love’s Labour’s Lost was first performed at Titchfield.

Wells – now the Director of the Shakespeare Birthplace Institute no less – describes the book as….

……’charming’….

…..but finally dismisses the book as….

‘semi-fiction’.

At least Stanley used the word ‘semi’!

He promised to write his own book on Will and Harry – but it has never seen the light of day.

*********

On the way back to West London on the train, Stewart shared an amazing coincidence with Your Cat.

His mother had been a talented tailoress – and had worked in the rag trade at Malone’s old house in London W1.

She managed to get a flat round the corner for her son – where he lived for seven years.

Now the extraordinary thing is that Malone’s house was in Langham Street –

….which was on property once owned by the Earl of Southampton…..

…..and which leads directly into…..

Great TITCHFIELD Street!!!

‘Bye now!