(It’s best to read Parts One and Two first. The Story continues…)

Mary Southampton summons Will…..

She has found out about the liaison between Will and Harry and is furious. But Will reminds her that her own love once crossed barriers of class.

Can’t she give her blessing to one that crosses barriers of sex?

She does – and Harry and Will travel to Europe in 1593 – as spies for the Earl of Essex and to celebrate their love.

In Spain Will and Harry see Titian’s paintings of Venus and Adonis...….

…..and The Rape of Lucrece..

They then travel on to Rome – where they see the newly erected obelisk in front of St. Peter’s…..

……and buy Italian novellas that Will transforms into plays.

When Harry and Will return to England, they find that Marlowe has been killed in a gay brawl – and that Kyd, under torture, has betrayed Marlowe’s atheism to the authorities. Mary Southampton commissions a narrative poem from Will based on Titian’s Venus and Adonis – and he uses the same colours in his verse that the artist does in his painting.

The poem has gay undertows – but basically celebrates the idea of heterosexual love – which remains unfulfilled.

Mary still hopes that her son will one day marry.

Harry is nominated for the Order of the Garter and Will warns him to be careful about his promiscuity with lower class young men, as this could be used against him politically – as indeed it was at his trial after the Essex Rebellion in 1601.

In 1594 – as we have seen – Harry commissions a poem from Will based on The Rape of Lucrece.

This is a massive chance for Will to write a serious poem – and he retires to Stratford to write it – again drawing on Titian’s original colours. But he neglects to write love-sonnets to Harry.

George Chapman…..

…….an older, impoverished poet – seizes his chance and starts to write poems to Harry that out-flatter even Will’s.

Will is desperate as he sees his source of income drying up – but Mary Southampton comes to his aid.

She commissions Will to write A Midsummer Night’s Dream to celebrate her wedding, in 1594, to Sir Thomas Heneage, at Copt Hall in Essex.

Despite the terrible summer weather, this play is such a triumph that Harry dumps Chapman and gives Will the famous present of £1,000. Will and Harry resume their affair – with lapses, it must be admitted, on both sides.

But Will finds it disturbing that Harry never shows any signs of guilt on his face…

In August 1596 Will’s son, Hamnet, dies. Will, ironically, is working on a new version of Hamlet at the Swan Theatre and has no time to mourn properly. He goes off the rails and is bound over to keep the peace – along with a bunch of low-lifers and prostitutes – after threatening violence to one William Wayte.

As a result Harry cannot be seen with Will – but in time, the two men resume their liaison, and Harry becomes Will’s surrogate son as well as his lover.

But finally Harry does fall in love with a woman – Elizabeth Vernon……

……a poor cousin of the Earl of Essex and lady-in-waiting to the Queen. Harry asks Will’s help to gain her favours by writing a love-play they can perform at Titchfield – Romeo and Juliet’

Will is ambivalent about this – and creates the disturbed figure of Mercutio for himself to play. But in the end he realises that he still has a spiritual relationship with Harry – ‘the marriage of true minds’.

Politics now take over from love. Both the Earl of Essex and Harry want to depose Queen Elizabeth because she will not name her successor – and they fear a civil war will ensue. Also Elizabeth refuses to give freedom of worship to Catholics – a cause Essex supports, though he is a Protestant.

Will is recruited into the plot – and is sent to Scotland in 1599 to persuade King James to invade England by performing Macbeth. This play prophesies – through the Three Witches – that the Stuart line will take over the throne of England as well as Scotland.

It also condemns the Macbeths for killing their royal guest – in the way Elizabeth has beheaded James’s mother, Mary Queen of Scots, when she sought refuge in England.

Will, though, realises that the rebellion is lost when Essex fails to quell an uprising in Ireland. He writes Julius Caesar to show how badly rebellions can go – but Essex and Harry go ahead with theirs and have the Chamberlain’s Men put on Richard II – a play about the deposition of a King – on the eve of the Essex rebellion.

Queen Elizabeth famously says: ‘I am Richard – know ye not that?’

Will flees to Scotland in a state of suicidal despair. Essex is beheaded – but Harry’s death sentence is commuted to life imprisonment in the Tower, where he becomes so ill people fear he will die.

But Elizabeth herself dies in 1603 and everything turns round. Will comes back to London and writes sonnets to his friend King James, imploring him to release Harry from the Tower: they are sent with a ‘wooing’ portrait of Harry…

…..depicting him with his hair loose, like a bride’s, and offering his left hand to the King.

Will writes:

Ah wherefore with infection should he live

And with his presence grace impiety,

That sin by him advantage should achieve

And lace itself with his society?

[Why should Harry still be locked up in the Tower of London, living with ‘infection’: (1) The literal infection of the Tower with its vermin (2) The moral infection of being imprisoned with criminals and (3) The infection of his own illness – his arm is still in a sling. And why should he give the grace of his being to sinful fellow convicts and allow them to hobnob with him as equals?]

The Sonnets do the trick – and on 5th April, James VI and I writes to the Privy Council:

‘Because the place is unwholesome and dolorous to him to whose body and mind we would give present comfort, intending unto him much further grace and favour, we have written to the Lieutenant of the Tower to deliver him out of prison presently.’

Harry is released from the Tower on 9th April, 1603 and Will writes a sonnet of pure joy.

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world, dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Suppos’d as forfeit to a confin’d doom.

[Neither my own anxieties nor the predictions of everybody else about the future can stop the release from the Tower of my lover – whom everyone thought would die in prison]

The mortal Moon hath her eclipse indur’d,

And the sad Augurs mock their own presage;

Incertainties now crown them-selves assur’d,

And peace proclaims Olives of endless age.

[Queen Elizabeth – the Moon-Goddess – has proved to be a human being after all. She has died – and those who predicted strife and civil war at her death have been proved wrong and laugh at what they themselves prophesied. Anxieties have given way to confidence, and the peace that has greeted the accession of King James promises peace for all time].

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh and death to me subscribes,

Since spite of him I’ll live in this poor rime,

While he insults ore dull and speechless tribes;

[The accession of King James has been like a healing balm to my beloved Harry, who now looks young and well. Even death now supports my writing since I will live on in this, my second-rate verse, while death triumphs over whole swathes of dim-witted and inarticulate people].

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

[And this poem, Harry, will be your monument – when the crests and brass tombs of tyrants like Queen Elizabeth will be in ruins].

‘Crests’ is a coded dig at Elizabeth. She once described herself as ‘cloven and not crested.’ Here Will gives her a crest and turns her into a man – a rumour about Elizabeth that had circulated for years. But even her crest – her honorary penis – will crumble into dust.

Will had met Harry in the summer of 1590. Their relationship – with all its infidelities and ups and downs – had lasted a full thirteen years.

The pasteboard obelisks set up on James’s coronation route were blown down by the wind….

– but they reminded Will of the genuine obelisk he and Harry had seen in Rome – and Will compared his love with Harry to the eternity of its stone.

But their affair was soon to end. It had survived Harry’s marriage to Elizabeth Vernon – which proved a very happy one – and had survived the birth of daughters to the couple. But in 1605 everything changed. Elizabeth produced a son.

Harry, by this time, had grown disenchanted with the gay world of James’s Court. He had hoped to become the King’s favourite – but, although only thirty, he was too old for James. The younger sons of the Countess of Pembroke – William and Philip Herbert – became the King’s favourites. Harry was marginalised.

Harry, alienated by events, wanted his son – named James after the King – to become a brave and masculine soldier.

Will, the Old Player, had to go.

So, not only had Will lost his real son – he had now lost his surrogate son as well.

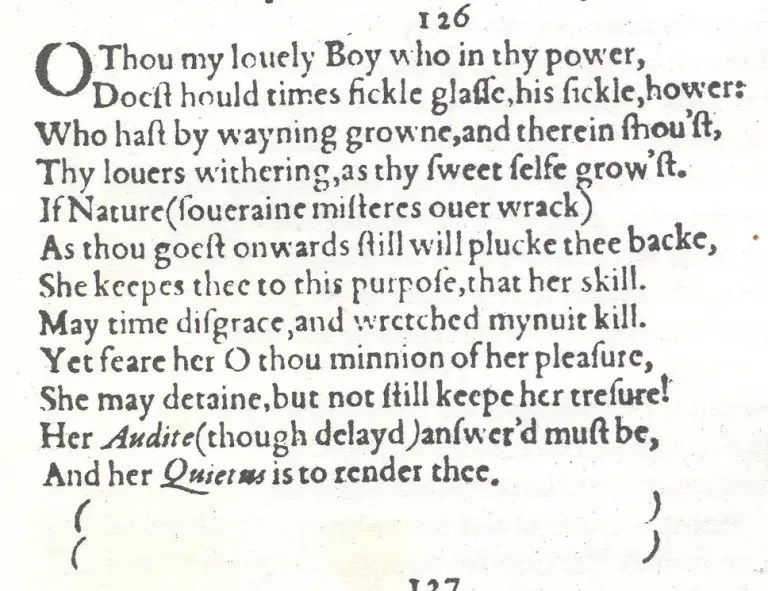

He responds by writing Harry a sonnet of pure poison: the phrase ‘lovely boy’ is bitter and sarcastic.

O thou my lovely Boy who in thy power

Dost hold time’s fickle glass, his sickle’s hour:

Who hast by waning grown, and therein show’st

Thy lover’s withering, as thy sweet self grow’st;

[Harry, you seem to have complete control of Father Time’s hour-glass and his sickle – with which he cuts life away. You have enacted the miracle of growing bigger by diminishing: you have waned but your other ‘self’ – your baby son – has waxed. But as your baby grows – and is given all your attention – I, your lover, am withering away from your neglect].

If Nature (sovereign mistress over wrack)

As thou goest onwards still will pluck thee back,

She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill

May time disgrace, and wretched minutes kill.

[If Dame Nature – who is the supreme controlling mistress of decay – keeps you unnaturally young – by preserving your ‘loveliness’ and giving you a son – her motive for doing this is to humiliate Father Time and destroy his pitiful minutes.]

Yet fear her, O thou minion of her pleasure;

She may detain, but not still keep her treasure!

Her Audit(though delayed) answer’d must be,

And her Quietus is to render thee.

[But be very frightened of your mistress, Dame Nature – you plaything of her lust. She can hold on to objects that she values – but can’t keep them. Her final invoice to Father Time must be honoured – and when she settles her bill she will ‘render’ you in two ways. (1) By giving you back to time – and (2) by breaking your body down like meat.]

This Sonnet is NOT even a Sonnet. It is only twelve lines long – and where there should be a clinching couplet, Will has put two pairs of brackets.

I

It looks like a grave – yawning open for Harry’s body.

Will wants his old lover dead.

Will was clearly going through a crisis – a break-down even – and it led on to some of his darkest, most nihilistic plays – the bleakest being King Lear. He smashes down the play’s original happy ending – and finally mourns for his son through Lear’s grief for his dead daughter.

And he took his revenge on Harry four years later by publishing all his intimate sonnets to him.

He gets his publisher, T. T. – Thomas Thorpe – to wish Harry ‘All Happiness’ – as Will does, as we have seen, in his dedication to Lucrece – and Thorpe – by describing himself as ‘the well-wishing adventurer’ who is ‘setting forth’ – references Harry’s ship – ‘The Sea Adventure’ – which left Plymouth for Virginia on 2nd June 1609 – a fortnight after the Sonnets had been published.

But in what I believe is Will’s final sonnet – 146 – he resolves to enter on a spiritual path away from worldly excess, and, in his words….

……..feed on death

In The Tempest Prospero says: ‘Every third thought shall be my grave’ – and in his final plays, Will seems to have come to accept the way things are.

William Davenant describes how, when he was a boy, Will would ‘cover his face with a hundred kisses’ when he visited him in Oxford, so perhaps Davenant had come to replace both Hamnet and Harry in Will’s heart, mind – and soul.

With the Sonnets, Will included a narrative poem ‘A Lover’s Complaint’. In this he splits himself into two – and has a conversation with himself. One half of Will is a young woman who has fallen in love with a psychotic young man whose ‘browny locks hung in crooked curls’ – not unlike Harry Southampton’s.

And, very much like Harry he…..

did in the general bosom reign

Of young, of old; and sexes both enchanted.

His other persona is….

A reverend man that grazed his cattle nigh–

Sometime a blusterer, that the ruffle knew

Of court, of city…

The O.E.D. guesses ‘blusterer’ means ‘boaster’ – but it could equally be a bombastic actor who ‘struts and frets his hour upon the stage.’

The young woman tells the older man how, like others, she fell besotted with the young man and…

Threw my affections in his charmed power,

Reserved the stalk and gave him all my flower.

But the young woman finally wises up….

For, lo, his passion, but an art of craft,

E’en there resolved my reason into tears;

There my white stole of chastity I daff’d,

Shook off my sober guards and civil fears;

Appear to him, as he to me appears,

All melting; though our drops this difference bore,

His poison’d me, and mine did him restore.

[His passion was an artful, bogus one that transformed my rational mind into tears. There I took off my white dress of chastity, shook off my ‘sober guards’ – my moral protection and abstention – and ‘civil fears’ – fear of abandoning propriety and even the law itself – and appeared to him in same ‘melting’ – weeping and ejaculating state – as he appeared to me – with this difference: his ‘drops’ – tears and semen – poisoned me while mine made him better.]

But the Young Woman comes to a most surprising conclusion…

O, that infected moisture of his eye,

O, that false fire which in his cheek so glow’d,

O, that forced thunder from his heart did fly,

O, that sad breath his spongy lungs bestow’d,

O, all that borrow’d motion seeming owed…

Would yet again betray the fore-betray’d,

And new pervert a reconciled maid!

If she had her time over, she would do it all again!

At the end of the day, Will was glad he had met Harry….

********

At the end of Stewart’s talk – ‘When Will met Harry’ – there was a lively and provactive Q. and A. session – which Your Cat will report on soon in a ‘Trixie Special’.

‘Bye now…