It’s best to read ‘Fear of Rejection’ Part 34 first.

End of 1595/6.

A bombshell.

Someone reports to Harry that Shakespeare has had an affair with a young lower class man while on tour in 1595.

Shakespeare tries to justify himself in the way Falstaff would have done….

……..had he been in the same situation…….

119. (120)

That you were once unkind be-friends me now,

And for that sorrow, which I then did feel,

Needs must I under my transgression bow,

Unless my Nerves were brass or hammered steel:

That you, Harry, once behaved with cruelty to me – by being unfaithful – proves, in fact, to be an act of kindness on your part. The sadness I experienced in the past I now inflict on you – unless I was completely insensible at the time and made of steel or brass.

For if you were by my unkindness shaken

As I by yours, y’have past a hell of Time,

And I a tyrant have no leisure taken

To weigh how once I suffered in your crime.

For if my infidelity caused you to suffer in the same way that your infidelity caused me to suffer then you have been in Hell and I, the tyrant who caused you this pain, didn’t pause to consider how much I suffered when you did the same to me.

O that our night of woe might have remember’d

My deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits,

And soon to you, as you to me then tender’d

The humble salve which wounded bosoms fits!

When we had our confrontation and argument I wish I could have recalled how painful your infidelity was to me and did what you did then: offer you the everyday balm for a wounded heart in the way that you offered it to me.

The ‘humble salve’ means (1) Harry’s tears (2) Harry’s love-making: his semen becomes like an ointment to heal Shakespeare’s hurt.

But that your trespass now becomes a fee,

Mine ransoms yours, and yours must ransom me.

Your infidelity now transforms itself into a payment. My sin now acts as a ransom for yours and frees it – and your sin does the same to mine.

120. (121)

A Gay Lib Sonnet – ‘Glad to be Gay’.

‘Tis better to be vile than vile esteemed,

When not to be, receives reproach of being,

And the just pleasure lost, which is so deemed

Not by our feeling, but by others’ seeing.

It’s better to behave badly than to be thought of as bad,( i.e. gay) when you are accused of being bad even if you are not! And refrain from what is a perfectly fine sexual pleasure (homosexual love) which is condemned, not in our own minds, but the minds of others.

For why should others‘ false adulterate eyes

Give salutation to my sportive blood?

Or on my frailties why are frailer spies

Which in their wills count bad what I think good?

For why should other people look and comment on my rampant libido? ‘Adulterate eyes’ = (1) ‘Men who, though they condemn my gay activity, commit heterosexual adultery themselves’ and (2) ‘Contaminated testicles’ = men with venereal disease. Why do men spy on my sexual peccadilloes when they are guilty of heterosexual misdemeanours themselves – men whose penises (‘wills’) condemn as bad what my penis thinks is good i.e. gay love-making.

There is also a play on William Shakespeare’s name.

No, I am that I am, and they that level

At my abuses reckon up their own;

I may be straight, though they them-selves be bevel:

By their rank thoughts my deeds must not be shown.

No. I am what I am – a gay man. And those who condemn me name their own sins. I could well be the one who is ‘straight’ and the men who condemn me bent (‘bevel’): I mustn’t be judged by their corrupted minds.

‘I am that I am’ is a reference to what God said to Moses when he asked God his name (‘Ego sum qui sum’ in the Vulgate translation. ‘I am that I am in the Geneva and King James Bible.)

Shakespeare often employs religious imagery in his celebration of gay sex. This time he even quotes God Himself!

Unless this general evil they maintain:

All men are bad and in their badness reign.

Unless the people who condemn me think all men are bad – contaminated by original sin.

121. (109)

O never say that I was false of heart,

Though absence seem’d my flame to qualify;

As easy might I from my self depart

As from my soul which in thy breast doth lie:

Shakespeare asks Harry never to accuse him of being untrue – though by being apart from him Shakespeare seemed to be less passionate in his love. He claims that it would be easier for him to part from himself than from Harry – where Shakespeare’s heart lies.

That is my home of love. If I have rang’d,

Like him that travels I return again,

Just to the time, not with the time exchang’d,

So that myself bring water for my stain.

You, Harry, are where my love has its true home – and if I have had an affair with somebody else, I have been like a traveller who journeys, then returns to his home, bending to the circumstance, not changing with it – and bring my tears to wash away the stain of my infidelity.

Never believe, though in my nature reign’d,

All frailties that besiege all kinds of blood,

That it could so preposterously be stain’d,

To leave for nothing all thy sum of good:

Even if my nature were completely overwhelmed with every sin that every kind of man commits, never think for a moment I could be so flawed in my judgement I would leave all your abundant goodness for a young man of no worth all.

‘Nothing’ can = ‘no thing’ = ‘no penis’. ‘Sum’ can equal ‘semen’ – drawing on the comparison of seminal fluid with money. See Sonnet 5. (4)

For nothing this wide Universe I call,

Save thou, my Rose: in it thou art my all.

Shakespeare says that the whole universe has no worth at compared to the worth of Harry – Shakespeare’s ‘Rose’. (The capitalisation is Shakespeare’s)

Shakespeare refers to Harry as ‘beauty’s Rose’ [Shakespeare’s capitalisation and italics] in Sonnet 2. (1) – a reference to the Southampton rose…

…..and to the way Harry’s family spelt and pronounced ”Wriothesley’ – ‘Ryosely’. [See Titchfield Parish Register].

122. (110)

Alas ’tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view;

Gor’d mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new.

I have been playing ‘away from home’ on tour – and have made a fool of myself – like a fool in his multi-coloured clothes. I have betrayed my conscience with penetrative anal sex and made my body, which should be reserved for you alone, available to anyone. I have committed old sins with new partners.

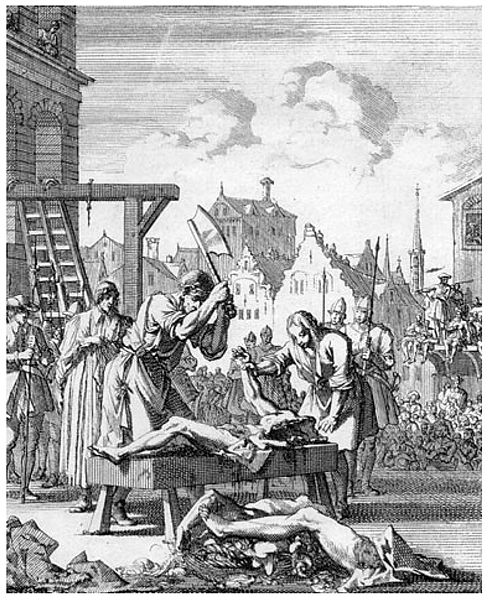

‘Goring’ = ‘gay, penetrative sex’ is used in Venus and Adonis. The boar attempts to ‘kiss’ the beautiful Adonis – and in doing see gores him to death in the groin. ‘Death’ in Shakespeare can = ‘orgasm’.

‘Tis true, ’tis true; thus was Adonis slain:

He ran upon the boar with his sharp spear,

Who did not whet his teeth at him again,

But by a kiss thought to persuade him there;

And nuzzling in his flank, the loving swine

Sheathed unaware the tusk in his soft groin.

Most true it is, that I have lookt on truth

Askance and strangely: but by all above,

These blenches gave my heart an other youth,

And worse essays prov’d thee my best of love.

The fact is, Harry, I lied to you. But these ‘sidelong glances’ (‘blenches’) (1) Made me young again (2) Gave me another young man, like yourself, as my sexual partner. And by testing out an inferior young man, it has made me realise that you are the best.

Now all is done, have what shall have no end:

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A God in love, to whom I am confin’d.

Now my affair is over have the thing that shall never end – my love for you. I will not try to sharpen my sexual appetite on a new friend – like sharpening a knife – which tries the patience of my older friend, you Harry – ‘A God in love’ = (1) A Love God and (2) My supreme lover to whom I am bound to in adoration….

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

Then please welcome me back home, you, who are the next best thing to heaven itself – even to your ‘pure’ breast = (1) Morally upright (2) Virginally chaste. And ‘most most loving breast’ = (1) Repetition of ‘most’ to emphasise the abundance of Harry’s love (2) A cheeky reference to Harry’s own promiscuity – Harry loves ‘most’ young men.

123. (117)

Accuse me thus, that I have scanted all,

Wherein I should your great deserts repay;

Forgot upon your dearest love to call,

Whereto all bonds do tie me day by day;

Shakespeare says it is right for Harry to accuse him of neglecting to pay him all that is due to him – both as Shakespeare’s lover AND financial patron – and has neglected to give Harry the love that he owes him as his slave.

That I have frequent been with unknown minds,

And given to time your own dear purchas’d right;

That I have hoisted sail to all the winds

Which should transport me farthest from your sight.

Shakespeare also invites Harry to attack him for having sex with common place, lower class young men and wasting the time that Harry has paid for with his gift of £1,000. Shakespeare says he has hoisted his sails to the winds that will take him far from Harry.

Here Shakespeare picks up the image of himself as a little boat in Sonnet 90. (80) – from the section of Sonnets about the Rival poets.

The hoisting sail imagery is also likened to the erection of the penis in Sonnet 95. (86)

Book both my wilfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise, accumulate;

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your waken’d hate:

Shakespeare asks Harry to carefully note his ‘wilfulness’ [= ‘sexual exploits’ playing on ‘Will’ = (1) Shakespeare’s penis and (2) Shakespeare’s name] and his ‘errors’ = sins, mistakes and imperfections, moral and physical.

Shakespeare asks Harry to aim at him with his frown – but not to aim at him with a cross-bow to kill him out of hate.

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

Shakespeare says his defence in court would be that Shakespeare behaved badly to test the strength and truthfulness of Harry’s love for him.

124. (118)

Like as to make our appetite more keen

With eager compounds we our palate urge,

As to prevent our maladies unseen

We sicken to shun sickness when we purge.

In order to increase our appetite for food, we eat bitter, strong herbs to stimulate our taste buds and sometimes we take purgatives to prevent future diseases from taking hold of us.

A ‘compound’ was a prescription of several herbs rather than a single herb – a ‘simple’. Compounds were becoming fashionable in Shakespeare’s day and Shakespeare was critical of them. See Sonnet 85. (76)

Even so, being full of your nere cloying sweetness,

To bitter sauces did I frame my feeding;

And, sick of wel-fare, found a kind of meetness

To be diseas’d ere that there was true needing.

That’s why Shakespeare – because he was full of the sweet taste of Harry which nearly sickened him – ate sauces with a bitter taste – because ‘sick’ [= tired] of being well, it was appropriate that Shakespeare made himself sick before the real sickness occurs i.e. being sick of Harry himself.

‘Nere’ could also mean ‘never’ – and Shakespeare leaves it to Harry to chose which meaning he would prefer!

Thus policy in love, t’anticipate

The ills that were not grew to faults assured,

And brought to medicine a healthful state

Which, rank of goodness, would by ill be cured;

So Shakespeare’s plan – to anticipate problems in love before they occurred – actually created problems and made a healthy state of love become ill. Shakespeare had tried to cure an over-profusion of goodness by a dose of badness.

But thence I learn and find the lesson true:

Drugs poison him that so fell sick of you.

But Shakespeare says he has learnt from experience that the drugs he took to cure him of his love-sickness have poisoned him.

i.e. Promiscuous sex with lower class men has proved disastrous to Shakespeare’s love-affair with Harry.

125. (119)

What potions have I drunk of Siren tears

Distill’d from Limbecks foul as hell within,

Applying fears to hopes, and hopes to fears,

Still losing when I saw myself to win?

Shakespeare – looking back on his gay affair with remorse – claims that he was seduced by a magical potion distilled Satanically from the tears of mermaids. The affair has filled him with fear swinging to hope and hope swinging to fear.

Note: It is not the sirens tears that are evil: it is the way they are processed by Satanic alchemy.

The mermaid was a very positive image to Shakespeare as it represented the late, Roman Catholic, Mary Queen of Scots who was often likened to a mermaid.

What wretched errors hath my heart committed,

Whilst it hath thought itself so blessed never?

How have mine eyes out of their Spheres been fitted,

In the distraction of this madding fever?

Shakespeare wonders at how many mistakes his heart has made at the very time he thought it was blessed (1) With good fortune and (2) The approval of Heaven. Shakespeare claims that his very eyes have left their sockets in his insane passion for a young man.

O benefit of ill, now I find true

That better is by evil still made better;

And ruin’d love when it is built anew,

Grows fairer than at first, more strong, far greater.

Shakespeare finds that bad experiences bring their benefits. Good things, like Harry, are actually strengthened in their goodness by bad things – and the love that has been ruined by Shakespeare’s infidelity grows even stronger when it is rebuilt.

So I return rebukt to my content,

And gain by ills thrice more than I have spent.

So, Shakespeare says, having been rebuked for my infidelity I return to Harry, the man who makes me happy. And so I gain three times more than I have lost by my unfaithfulness.

To read ‘Reconciliation, Grief and Melancholy’, Part 36, click: HERE