The Background

First, what do we mean by Jacobite?

‘Jacobus’ is the Latin name for James – and the Jacobites were named after the followers of King James II who was crowned in 1685 and deposed three years later.

But ‘Jacobitism’ itself, as a philosophy, a movement and finally a romance, goes back to 1643, the fortieth anniversary of the coronation of King James VI of Scotland as King James I of England, and the end of the first year of the English Civil Wars.

Jacobitism started life as a song – written to a ‘sweet tune’ to which you could march – or dance – but whose lyrics, the writer insisted, must be sung ‘joyfully’. His name was Martin Parker – a hugely popular balladeer – as well as being, in his time, a vagrant, tapster, drunk and thief.

He was responding to a prediction made by John Booker, an eminent Astrologer who had successfully predicted the deaths of the Kings of Bohemia and Sweden – and was now predicting the downfall of King Charles I.

Parker’s ballad was originally titled ‘Upon the Defacing of Whitehall’ but soon became better known as ‘The King shall Enjoy his own Again’ or ‘The King shall come Home in Peace Again’. There are variations in the lyrics – but that is hardly surprising as the song was sung for over a hundred years.

It begins:

‘What Booker can prognosticate

Or speak of our Kingdom’s present state?

I think myself to be as wise

As he that most looks at the skies.

My skill goes beyond the depth of a pond

Or rivers in the greatest rain

By the which I can tell that all things will be well

When the King comes home in peace again’.

Parker sets himself up in opposition to Booker – not because he has more skill in prediction but because he has more common sense. Between 1642 and the summer of 1643 there were no fewer than 14 battles between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists.

Charles I had left his Whitehall Palace and set up a base in York, but at the end of 1642 he was denied entry to London by Parliamentarian troops at Turnham Green. He set up his base in Oxford which, became a Royalist stronghold way into the eighteenth century.

Parker is saying that while the King is away from his Palace in London, there will never be peace in the land. For Parker this is not prophecy – it is fact. And by writing so directly – and vividly – in the first person, he invites you to join in with him – and become him.

The ballad continues:

‘Though for a time you see White-hall

With cobwebs hanging over the wall

Instead of silk and silver brave

As formerly it used to have;

In every room, the sweet perfume,.

Delightful for that princely train;

The which you shall see, when the time it shall be

That the King comes home in peace again’.

Parker pictures the neglected Whitehall which Charles I’s father, James I, had beautified with the help of Inigo Jones. Charles himself had commissioned paintings from Peter Paul Rubens, depicting King James as Solomon – the King of Peace.

Even though Parker has been penniless at times, he enjoys the surrogate pleasure of describing King Charles surrounded by beautiful sights and smells.

‘For forty years the Royal Crown

Hath been his father’s and his own

And I am sure there’s none but he

Hath right to that sovereignty.

Then who better may the sceptre sway

Than he that hath such right to reign?

The hopes of your peace, for the wars will then cease

When the King enjoys his own again’.

Parker here celebrates the Divine Right of Kings which was introduced to England by James I. He believed that the monarchy was – in his own words to Parliament in 1610 – ‘the most supreme thing on earth’ and that ‘kings are God’s lieutenants sitting upon God’s throne’. The King’s successor should share the same blood line so that peace – not war – would follow the death of monarchs.

Oliver Cromwell was coming into prominence in 1643 when he was made a Colonel in the Parliamentarian Army.

Parker foresaw his coming threat, and challenges his right to ‘reign’ as he is not a Stuart. The ballad, in its early version, concludes with:

‘Till then upon Ararat’s Hill

My hope shall cast her anchor still

Until I see some peaceful dove

Bring home that branch which I do love

Still will I wait till the waters abate

Which most disturbs my troubled brain

For I’ll never rejoice till I hear the voice

That the King comes home in peace again’.

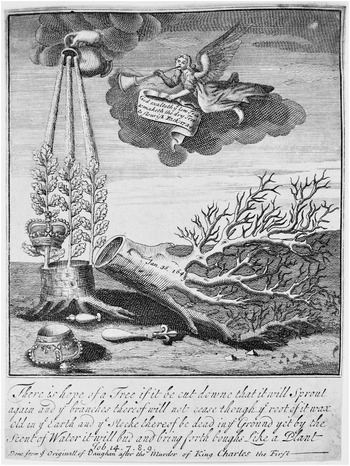

Parker refers to the story of Noah – whose ark came to rest on Mount Ararat. Like him, Parker will only know peace of mind when the dove returns with an olive branch.

Parker did not put his name to this ballad as it would have been dangerous to do so. He did, though, put his initials on one which supported the Anglican Bishops – and was threatened with jail by the Puritan Parliament.

He fell silent – but he had touched a nerve with the ‘ordinary’ English public. He captured their love of the Royal Family and their longing for peace.

Booker, of course, proved correct in his prediction about the decline of Charles I – even if he didn’t foresee his execution. But Parker had a poetic, even spiritual, truth about his poem that was to grow with time – especially when Charles I’s son, Charles II, had to flee to France. He became ‘the King Over the Water’ and people wanted to him to fly back, like Noah’s dove, to his own country.

This was to happen five years later, in 1660, when red wine flowed in the fountains of London and King Charles had a huge maypole erected where St. Mary le Strands Church now stands. The crowds at his Coronation danced round it and sang ‘The King shall enjoy his own again’.

Parker, who had died four years earlier, had been accused of being a Roman Catholic because of his support for the Stuarts – and Charles I and Charles II had both married Catholic wives. Charles II converted to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed in 1685, but his brother, James, who became King James II, was by then an open follower of ‘the Old Faith’.

James II wanted freedom of worship in Britain and appointed Catholics to leading positions in government and the army. This alarmed the newly formed Whig Party, who wanted to get rid of both Roman Catholicism and the Divine Right of Kings. So the King sought the support of the newly formed Tory party – and in March, 1686, the support of the Scottish Lords.

An anonymous Scottish poet wrote a poem called ‘Caledonia’s Farewell’ to the Duke of Perth and the Duke of Queensbury, urging them to travel down to London to kiss the hands of King James to prove that ‘Caledonia loves the Stuarts well’.

The poem has a strange, esoteric footnote – explaining, that because King James II was the hundredth and eleventh Scottish King since Fergus, he had a right to the throne by numerology as well as blood.

The ‘111’ can convert to an equilateral triangle which, for the ‘Grecians denominated a King’. The poet added the information that the base of the triangle represented Scotland – from which the Stuart line originated – with England on the left and Ireland on the right.

The Jacobites now had a symbol as well as a song. The great esoteric scholar Marsha Keith Schuchard tells us that supporters of the Stuarts would include a triangle formed of three dots in their correspondence.

But as we can see from the medallion struck in Paris by a Masonic Lodge to commemorate Benjamin Franklin…..

……the triangle was also a symbol of Freemasonry.

‘Caledonia’s Farewell’ was published, it is thought, by a group of Edinburgh Freemasons. Certainly the poem itself praises the loyalty to the King of ‘builders’ and ‘the cementing trade’. It also mentions Euclid and ‘the Architect’ – Harim Abiff – both central to Masonic philosophy and practice.

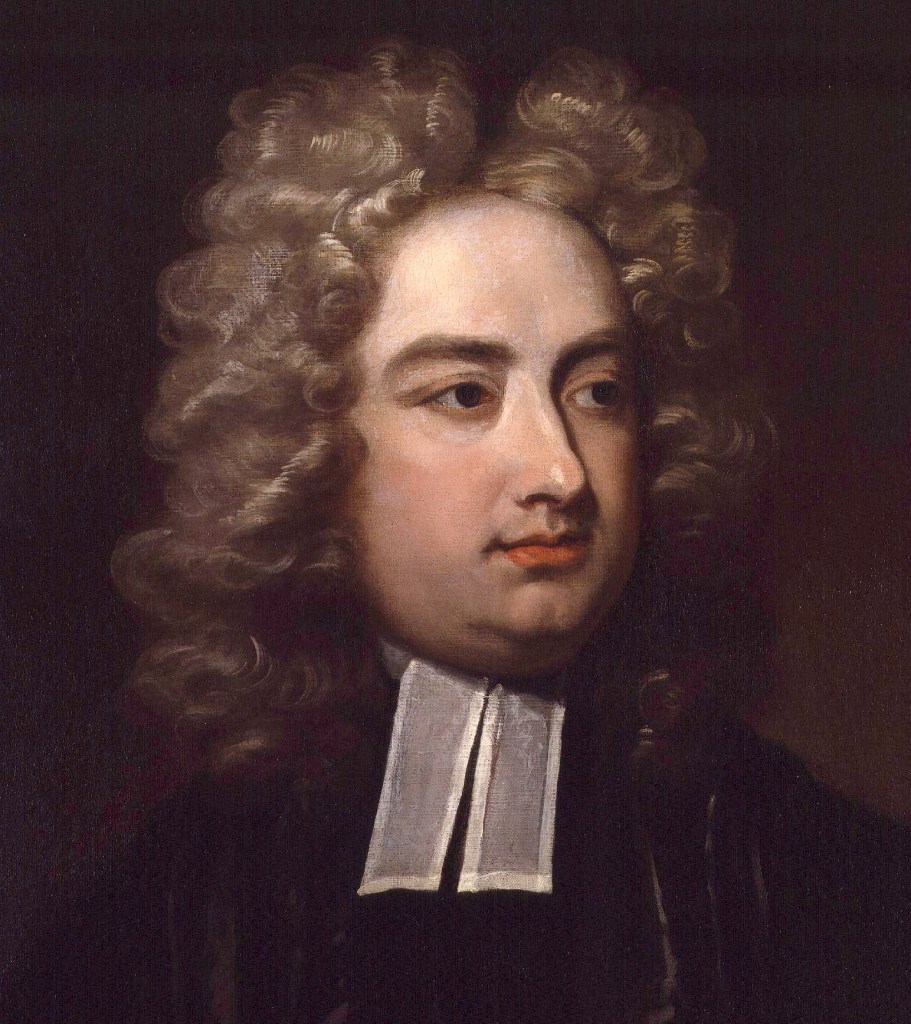

Some Masons believe that Freemasonry began in London in 1717 – but that wasn’t the view of Jonathan Swift – who was friends with many of the people engaged in building St. Mary le Strand.

In the persona of ‘the Grand Mistress of the Female Freemasons’ Swift claims that Freemasonry started in Scotland at the time of King Fergus ‘who reigned there more than two thousand years ago’ and was the ‘grand master’ of the Kilwinning Lodge ‘the antientest and purest now on earth’.

Masonry, the Grand Mistress claims, was first begun by Scottish Druids who worshipped – and carved – oak trees. The movement, influenced by Jewish people, developed into Rosicrucianism and ‘Cabala’ [Swift’s spelling]. The Knights Templar later ‘adorned the ancient Jewish and Pagan mystery with many religious and Christian rules’.

Stone came to replace oak as the central symbol of Freemasonry and, according to ‘Swift’, ‘after King James VI’s accession to the throne of England, he revived masonry, of which he was grand master, both in Scotland and England. It had been entirely suppressed by Queen Elizabeth, because she could not get into the secret’.

How much of this is ‘literally’ true is difficult to say – but a number of modern historians believe that Freemasonry did, indeed, originate in Scotland and was developed by King James VI who brought it into England in 1603.

King James’s son, Charles I, attended Masonic ceremonies at Somerset House in the Strand and he too had links with the Scottish Freemasons even before the Civil Wars.

In 1638 Henry Adamson, a Scottish poet and Freemason, had written to King Charles I asking him to repair the great stone bridge at Perth. He predicted to his fellow Masons:

‘Therefore I courage take, and hope to see

A bridge yet built although I aged be’.

He then explains to his brothers why he is so certain this will happen:

‘For we be brethren of the Rosie Crosse

We have the Mason Word, and second sight,

Things for to come we can foretell aright,

And shall we show what misterie we mean

In fair acrostics ‘Carolus Rex’ is seen.

Describ’d upon that bridge in perfect gold…’

‘Carolus Rex’ is King Charles I – and it has been suggested that the acrostic reads ‘Roseal cross’ – a reference to Rosicrucianism.

Etienne Morin, an eighteenth century French sea-faring trader and leading Freemason, claimed that Charles I’s son, Charles II, also had links with the Freemasons in Europe and formed Masonic Lodges in France when he was in exile.

Another eighteenth century Freemason, Nicholas de Bonville, also suggested that a network of Freemasons – led by Colonel George Monck (who was said to have converted from the Parliamentary Army to Freemasonry in Scotland) engineered King Charles II’s Restoration to the British Throne.

We know from papers left by Thomas Hearne, the Jacobite underkeeper of the Bodleian Library, that Charles II, when in exile, adopted for his personal symbol the ouroboros – the snake that feeds on itself.

This symbolised the immortality of the Stuart line and its constant return, but it was also associated with Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism, as we can see when we look at the Franklin Medal again, where it symbolises Craft ideas of renewal and rebirth.

Another symbol emerged at the Restoration which was linked to both Freemasonry and the Stuarts was the oak tree – worshipped by the Druids – which came to represent Charles I – chopped down by Cromwell.

Saplings, though, spring from the oak tree, which represent Charles I’s sons, Charles II and James II.

Charles II also famously hid in an oak tree, disguised as a peasant, after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester.

The idea grew that he took on himself the power and fertility of the oak – which loses its leaves in winter but regains them in summer. He became associated with fruit and flowers, pomegranates and grapes – and all the joys of spring. Charles II is celebrated as the Garland King or Green Man on Oak Apple Day in parts of England up to present times.

Charles II’s wife – Catharine of Breganza – was unable to bear children, but Charles himself was certainly fecund: he fathered at least fourteen of them outside his marriage, two with the beautiful Nell Gwn…

Charles’s brother James II managed to produce a son with his wife, Mary of Modena in 1688 – also named James. James II’s daughters, Mary and Anne, were both Protestants, but now he had a son, Whigs feared it would be the start of a Roman Catholic dynasty. King James’s enemies put it around that the baby boy had been smuggled into the Queen’s bedchamber in a bedpan.

Seven notables – including aristocrats and the Bishop of London – invited the Calvinist William of Orange – who was married to King James II’s daughter Mary – to invade Britain.

King James was arrested, but escaped from his Dutch guards and fled abroad.

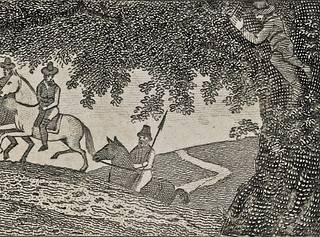

Loyalist Jacobites rose up in Ireland and Scotland, but King William and the Government Army defeated them. The Scottish Highland Jacobites – under John Graham of Claverhouse – known as ‘Bonnie Dundee’ – had a famous victory at Killiekrankie…..

.

……..but Dundee himself was shot and killed in the battle.

Political songs started up again and many Jacobite scholars believe that ‘God save the King’ began life as a Jacobite anthem. It existed in a Latin form sung in James II’s Catholic Chapel in Whitehall and its lyrics, especially ‘Send him victorious’, sound as though they are addressed to a ‘King over the Water’. The anthem – which is also engraved on Jacobite drinking glasses….

…..has the phrase ‘Soon to reign over us’ and asks God to bless ‘The True Born Prince of Wales’ – which sounds like a reply to the bedpan scandal.

The song goes on to bless what is clearly the Roman Catholic Church and hopes that it will remain….

‘Pure and against all heresy

And Whigs’ hypocrisy

Who strive maliciously

Her to defame’.

The last verse runs….

‘God bless the subjects all,

And save both great and small

In every station.

That will bring home the King,

Who hath best right to reign

It is the only thing

Can save the Nation’.

This is a re-run of ‘The King shall enjoy his own again’ – which the Irish Jacobites were still marching to in the 1690s and which the Bristol Jacobites were still dancing to when Queen Mary died in 1694…

James II died in exile in 1701. The Pope in Rome immediately acknowledged James’s son as ‘King James III’ ….

…….but in London the Act of Settlement was passed the same year which decreed that only a Protestant could become King or Queen of England.

King William died the following year – following a fall from his horse which had stumbled over a molehill. The Jacobites had a new coded toast: ‘To the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat.’

James II’s younger daughter, Anne, a High Church Anglican, became Queen of England.

Loyalists hoped that Queen Anne and her husband, Prince George of Denmark, would produce heirs to secure the Stuart line – but though Anne had 18 pregnancies, none of her children survived.

When Prince George died in 1708, it became clear to everyone that Anne – then 43 – would have to nominate her successor. She was rumoured to favour her half-brother, James III, known as ‘The Pretender’ to his enemies.

Most of the Tories also backed James III and tried to persuade him to become a Protestant.

The Whig Party, however, favoured Sophia of Hanover, but she was approaching 80. Failing her, they would invite George Louis, the Elector of Hanover, to become King of Britian.

He was 54th in line to the throne, but a Protestant.

It was now a waiting game to see who Queen Anne would nominate in her will.

Meanwhile, Militia Men marched through the City of London in 1711 – to the tune of ‘The King shall enjoy his own again’….

© Stewart Trotter February 2025

[Please read ‘Is St. Mary le Strand a Jacobite Church? (II of III)]