(Please read Part I first)

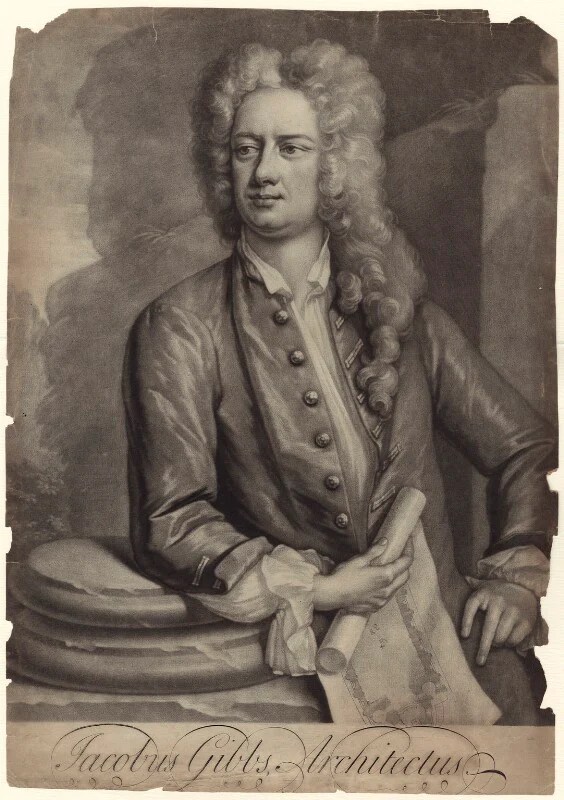

The Architect of St. Mary le Strand

James Gibbs was seven years old when Bonnie Dundee was killed at Killiecrankie. He was born in Aberdeen to Roman Catholic parents who continued to practice their faith, even though it had been banned in Scotland. Young James was a devout Catholic – so devout he determined to go to Rome to train as a renegade priest. When Gibbs’s parents died, around 1700, he sold their isolated home to the Aberdeen Freemasons to use as a Lodge.

There had been Lodges in Aberdeen since the beginning of the sixteenth century – but they had been for working Stonemasons – and were like early Trades Union. Many of the Masons were unlettered – so rote-learning took the place of books, and handshakes and passwords took the place of certificates of proof of training. These were called Operative Lodges.

But in 1670 a Speculative Lodge was established in Aberdeen for those not in the building trade but interested in the history and philosophy of Masonry – and eager to embark on its course of self-improvement and enlightenment. All that was required was a nomination, a wish to enter a supportive brotherhood and a belief in a Supreme Architect of the Universe. So Jewish people, Roman Catholics and even Quakers, were welcome as Brothers to the Aberdeen Lodge.

Gibbs was a Freemason: James Anderson in his ‘Constitutions of the Freemasons’ describes him as ‘Bro. Gib’ and describes him walking in a Masonic procession in 1721 to the ‘levelling’ ceremony at St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church. It is perfectly possible Gibbs’s father was a Mason and that Gibbs, then 18, was ‘fast-tracked’ into the Aberdeen Lodge before he left for Rome.

We know that on the way there he visited Paris and may well have introduced himself to the exiled Catholic Stuart family. But when he arrived at Rome, he was so terrified of the Italian Jesuit who ran the Scots College that he left without taking his oath. He became apprenticed to some of the top architects in Rome, including Carlo Fontana, sold his water colours to aristocrats on their Grand Tour and acted as a guide.

Word reached him that his half-brother was dying, so he returned to Scotland in 1709 – but arrived too late. There was no money for him in his native country – so he journeyed down to England.

But there was no money for him there, either.

For ‘four years he starved’ and wrote that he had ‘a great many very good friends here … of the first rank and quality … but their promises are not a present relief for my circumstances.’

But being ‘of good parts and virtuously inclined and well disposed’…….

……Gibbs was lucky enough to catch the eye of John Erskine, 23rd Earl of Mar – a fellow Scottish Freemason and architect – who was in London working on the Union between England and Scotland.

Mar called Gibbs ‘Signor Gibbi’, gave him some minor architectural work in Alloa in Scotland and appointed him Surveyor of Stirling Castle. The money for Gibbs’s Surveyorship soon ran out.

But Mar had another idea….

Two years after Gibbs came to England, there had been a massive power shift at Queen Anne’s Court. The Queen had fallen out with her friend, Sarah Churchill, an ardent Whig.

So the Tories were back in power.

They came up with a plan to build fifty new churches, in the High Church Anglican style, in the suburbs of the City of London – to celebrate the piety and power of the Stuart dynasty. Queen Anne – like all the Stuarts – loved architecture – and gave her full backing to the scheme.

Mar introduced Gibbs to Sir Christopher Wren, who was then in his late 70s.

A Tory (he sat as an M.P. in the Loyal Parliament to support James II), a Jacobite (he had been Surveyor of the King’s Works to Charles II) and a Freemason (to this day his gavel is on show at the Museum of Freemasonry in London), he became ‘much Gibbs’ friend and pleased with his drawings’. Wren and Mar came up with a scheme to make Gibbs one of the two surveyors on the Commission for Building 50 Churches.

But there was a problem. John Vanbrugh, the playwright and architect, was on the Commission as well….

……and he and Wren hated each other. Vanbrugh was also a Freemason – but he was a Hanoverian Freemason. An irrevocable split had begun in the Brotherhood…..

Vanbrugh supported a different candidate for the Surveyor’s post – John James – ten years older than Gibbs and with a lot more experience. Wren and Mar had to call on the help of Queen Anne’s proto-Prime Minister, Lord Harley (Tory, Jacobite and Freemason) her Chancellor of the Exchequer, Robert Benson – newly created Lord Bingley (Tory, Jacobite and Freemason) and even her Physician, Dr. Arbuthnot (Tory, Jacobite and Freemason) to push the appointment through….

ST MARY LE STRAND CHURCH

By 1714 the Maypole that Charles II had erected in the Strand had fallen into disrepair and the Commission decided to replace it with a church – St. Mary le Strand. It would be on the Processional Route from Westminster to St. Paul’s Cathedral and Queen Anne loved processions.

The Church would also raise the tone of the area which had become a notorious red light district since the Restoration.

It was planned to place a statue of Queen Anne over the Church’s porch. But the Jacobites on the Commission came up with an even more striking idea. A huge column – like Trajan’s Column in Rome – even higher than Wren’s Monument to the Great Fire – with an internal spiral staircase and viewing platform, four guardian lions round the base, and a statue of Queen Anne at the top.

Gibbs, who had submitted a design for the Church, but had lost out to Thomas Archer, was given the consolation prize of designing the column.

But the Queen’s health, which had never been good, was getting worse. By 8th July it was so bad the Commission considered a six week adjournment. On 15th July a Committee was set up ‘to confer together’ about the design of the Strand Church. If the Queen died, everything would change.

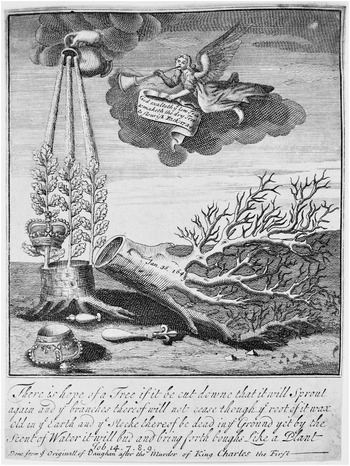

The Commission, though, took a chance and went ahead with the column. But on 1st August, 1714 the Queen did die.

Intestate.

Four days later work on the column was stopped…. and everyone started to plot…..

The Tory Party at the time was hopelessly divided, so the Whigs swept back into power. Sophia of Hanover had died a few weeks earlier, at the age of 83, so the Elector of Hanover was proclaimed King George I of Britain, France and Ireland.

To the Jacobites, of course, this was a catastrophe. Loyalty to the Stuart Family suddenly became treason. If you drank a toast to ‘James III’ you could be put in jail for two years. One poor soldier knelt as he toasted the ‘King over the Water’ and was flogged to death.

Secret Jacobite symbols had to be employed all over again – and new songs written – collected by James Hogg and published in two volumes in 1819 and 1821. Hogg – ‘the Ettrick Shepherd’…..

……who really had been a farm worker before he turned writer – is not always reliable and may even have forged some of the songs himself. But many are contemporary – and even those written later – when Jacobitism became a remembered romance rather than a movement – give us an insight into what people were thinking and feeling at the time.

‘The Blackbird’, though, which Hogg describes as ‘a street song of the day’ is genuinely contemporary:

In this a ‘fair lady’ sobs and laments the loss of her ‘blackbird’ – the code-word for James III who had a swarthy complexion and dark hair – like Charles II who was called ‘The Black Boy’ by his mother. A Spanish gene seems to have been introduced to the Stuart family by Charles II’s maternal grandmother, Marie de Medici….

‘My blackbird for ever is flown.

He’s all my heart’s treasurer, my joy and my pleasure,

So justly, my love, my heart follows thee;

And I am resolved, in foul or fair weather

To seek out my blackbird, wherever he be.’

Britain, in many Jacobite songs, became a woman, yearning for her beloved bird – in the way Parker had yearned for the return of the dove of peace.

Scottish Jacobites were particularly scathing about King George I. In ‘The Wee Wee German Lairdie’, a song in almost impenetrable dialect, the Scots display contempt for the new monarch, not only because he is small, but because, when word came to him that he was King of England, he was found hoeing turnips in his garden.

And though he was the King of England, he could not speak English…

‘The very dogs o’ England’s court

They bark and howl in German’.

If he ever tries to enter Scotland ‘our Scots thristle [thistle] will jag [prick] his thumbs’.

In another Jacobite song, ‘At Auchindown’, George I is described as ‘cuckold Geordie’ and in ‘Jamie the Rover’ there is a reference to the King’s ‘horns’:

‘In London there’s a huge black bull

That would devour us at his will

We’ll twist his horns out of his skull

And drive the old rogue to Hanover’.

George I’s wife, Sophia Dorothea of Celle, had been accused of having an affair with Count Philip Christoph von Konigsmark. The Count went missing – murdered, it was rumoured by George, who locked up his wife at the Castle of Ahiden.

She took her revenge by always referring to him as ‘Hagenschnaut’ – ‘Pig Snout’.

George was crowned on 20th October 1714 – provoking Jacobite riots in twenty diffferent English towns….

A fortnight later, a meeting of the Building Committee of the Commission for Building 50 Churches convened, chaired by Lord Bingley and composed of Dr. Arbuthnot, Sir Christopher Wren and his son (also called Christopher and also a Tory, a Jacobite and a Freemason).

Vanbrugh (newly knighted by King George and with Blenheim Palace to his credit) and Gibbs (only 30 and without a single public building to his name) ‘both laid before the committee two designs for the next church ‘to be erected near the Maypole in the Strand’. The committee judged both designs were ‘proper to be put into execution’ and ‘referred to Commissioners to make the choice.

At this point two pages have been ripped out of the Minutes book of the Building Committee…

Two days later the designs were submitted to the Commission itself – who, as usual, voted by secret ballot. Wren was not in attendance – but his son was.

Gibbs was awarded the commission. The Jacobites had won.

But Gibbs nearly lost the job. His mentor, the Earl of Mar, was the leading Jacobite in Britain and he led the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715.

It failed, of course, but it introduced the most powerful Jacobite symbol of all…the five-petalled White Rose.

According to Hogg, there was a gathering of Northern Jacobite men and women at the ruined Auchindown Castle in Scotland on 10th June, 1715 – the anniversary of James III’s birthday.

The Castle had been the temporary headquarters of Bonnie Dundee during the 1689 Rebellion, so the Jacobites met there to drink to the memory of Dundee and the health of James III.

They picked wild, white alba roses……

……then pinned them to their bosoms and bonnets and danced.

‘Of all the days that’s in the year

The tenth of June I hold most dear,

When our white roses all appear

For the sake of Jamie the Rover.

In tartans braw our lads are drest

With roses glancing on the breast

For among them a’ we love him best,

Young Jamie they call the Rover.’

Legend has it that the Earl of Mar’s Jacobite soldiers wore white ribbons in their bonnets, shaped into roses.

The famous ‘White Cockade’ had been born.

‘My love was born in Aberdeen,

The bonniest lad that e’er was seen,

But now he makes our heart fu’ sad

He’s ta’en the field with his white cockade.

O he’s a ranting roving blade!

O he’s a brisk and bonny lad!

Betide what may my heart is glad

To see my lad with his white cockade!’

The Earl of Mar fled from Britain at the end of 1715 and at the beginning of 1716 all the suspected Jacobites were thrown off the Commission for Building 50 Churches – including Wren, Arbuthnot, Bingley and Gibbs.

A rival Scottish architect called Colen Campbell had written anonymously to the Commission, accusing Gibbs of being a ‘Papist’ and a ‘disaffected person’. Gibbs was sacked as the Commission’s Surveyor and taken off the St. Mary le Strand project.

Gibbs of course denied the charges – which were completely true – and made the Commission an astonishing proposal. He would design and build the Church for nothing. His only condition was to take his designs away with him – ‘and no-one be allowed to take a copy…. he intending to engrave it for his own use’.

This was an offer the Commission could not refuse. King George had no interest in architecture – certainly not Anglican architecture – and the Commission wanted to wrap up the fifty church project as quickly and as cheaply as possible.

But they came to regret their decision. It meant they could not check that Gibbs was following the designs they had agreed to and, because they were not paying him, they could not control him.

Gibbs was also in a secret, coded correspondence with the exiled Earl of Mar. It is clear from the letters that Gibbs was working as a Jacobite agent – using codewords like ‘landlady’ for King James III and ‘Benjamin Bing’ for Robert Benson, Lord Bingley.

Mar wrote to Gibbs on 16th April 1716 that ‘Benjamin Bing in Westminster now ought to build the lodge for himself or someone else’ [using ‘building the lodge’ as a code for recruiting Jacobites] and hopes ‘it may come to be built upon the bank where it was designed’ [i.e. take over the running of Parliament in Westminster].

At this point Gibbs was even planning to join Mar in France.

Dislike of Hanoverian rule was growing in London and all the rest of the country. People feared a Lutheran King would bring back the bad old days of Cromwell.

There were two flash points in the year: the first was 29th May, Restoration Day, when the King had returned to England from exile. People now wore sprays of oak leaves, decorated their front doors with oak boughs and danced round oak trees and maypoles.

The lads took heart, and dressed themselves

In rural garments gay

And round about like fairy elves,

They danced the live-long day;

Around around an oaken tree

They danced with joy, and so do we.

The educated Jacobites would paint their oak boughs gold – in memory of Aeneas who plucked a golden bough from a tree so he could enter the underworld.

Jacobites identified the exiled Aeneas with James III – hoping that in the way Aeneas founded Rome, James would found a new Augustan Age when he was back in Britain..

The Freemasons also hoped he would bring back the fashion for building in stone. Protestant Kings favoured brick…

The second flashpoint was the 10th June – James III’s birthday, White Rose Day – when people carried and wore bunches of white roses.

Soldiers went through London, snatching oak leaves and roses from the people and arresting those who resisted. But all over the country people made fun of George I by brandishing turnips and wearing horns on their heads.

And, of course, everyone was still dancing and singing to ‘The King shall enjoy his own again’…

In November 1718 the Commission Surveyors got suspicious and visited the St. Mary le Strand building site. They were horrified by what they saw and recommended to the Commission that ‘a stop should be put to the extravagant carvings within the Church’.

In March the following year the Commission resolved that ‘Before Gibbs direct any further carvers’ or painters’ work for finishing Strand Church design and estimate to be laid before Board so that agreement may be made with artificers before they are put in hand. Copy to Gibbs’.

But Gibbs was off. Word had got round about the beauty of St. Mary le Strand, as Gibbs predicted it would, and work came flooding in. Interestingly he had been employed by Lord Burlington at Chiswick House….

– but Burlington diplomatically ‘sacked’ him when he was accused of Jacobitism. The reason for this – as Jane Clark, and later Ricky Pound, have argued – is that Burlington – seemingly a pillar of the Hanoverian Establishment – was in fact a closet Jacobite.

In a letter to King James III in October, 1719, the Earl of Mar compares the exiled Stuarts to the exiled Israelites and hopes that King George I – like Cyrus the Great of Persia who invited the Israelites to return and rebuild the Temple of Solomon – will invite the Stuarts to return to Britain.

Clark believes that Chiswick House was a Jacobite Temple – dedicated to the return of the Stuarts. It is full of discreet Jacobite symbols – discreet because they had to be…

One of mantlepieces has a King Charles II Green Man –

….another has thistles, and roses, and grapes and fleur de lyses….

The reason for the fleur de lyses is that, at the end of 1720, James III and his wife, Maria Clementina Sobieska, had a son, Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart – better known to the world as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’. At birth he was created the Prince of Wales and inducted into the Order of the Thistle. Jacobite astronomers claimed that a new star had appeared in the sky….

Now there was a distinct hope of a Stuart dynasty – and Chiswick House is full of the faces and bodies of putti and young men and women, encouraging Stuart procreation.

Some of them seem to have fleur de lyses in their hair…

And as we have seen, Freemasonry went hand in hand with Jacobitism from the very beginning. Chiswick House has a blue velvet room….

…..a colour associated with ‘Cabala’ Masonry (now called Third Degree Masonry) and a red velvet room…..

…….a colour associated with Knights Templar Masonry (now called Royal Arch Masonry).

Chiswick House is separated from the main family dwelling. It has no kitchen – but it does have a wine cellar and a spiral stairway – ideal conditions, Jane Clark argues, for Masonic Rites – designed to will the King over the Water back to England.

Could any of this apply to St. Mary le Strand?

© Stewart Trotter February 2025