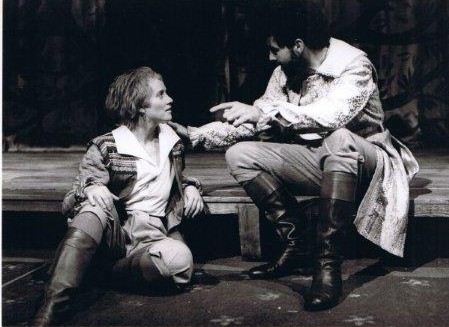

Karen Gledhill, in her highly perceptive letter, mentions Twelfth Night at the Northcott Theatre (in which she played a striking Viola) .

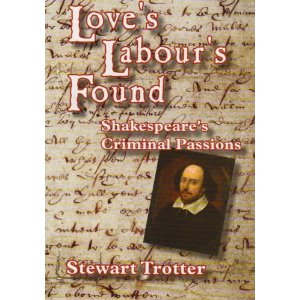

The Shakespeare Code believes readers might be interested in how this production came about.

It came from a dream.

In 1985, following a mystical experience in 1984, Stewart Trotter kept a dream journal. On 28 April he wrote:

Twelfth Night: winter and snow, and matter for a May morning. Fires to attract back the sun: cakes, ale and ginger hot in the mouth. The banishing of winter and the routing of the Puritan. But the final triumph of death and mortality.

On 29 April, the following day, he recorded how he could not ‘catch’ the dream of the night before (he equated ‘dreamwork’ with fishing):

The fish got away! A gleam of its tail and away!

But he then reflected further on the dream the night before:

But Twelfth Night set on a frozen river, a setting winter sun…Twelfth Night on Ice!

He followed his dream through: and on 23 October, 1985, the late B.A.Young, doyen of critics (who really could ‘paint the scene in words’) wrote in The Financial Times:

The glittering production of Twelfth Night, with which Stewart Trotter concludes his five years at the Northcott Theatre in Exeter, stands on a frozen pond that occupies not only all the stage, but also the extended forestage, reaching to the front row of the stalls.

Onto the ice are slid three trucks full of scenery that, to the designs of John McMurray, and under the guide of Feste on skates, become a small fit-up stage with a loose back-drop. Strips of carpet surround it on the ice, and, farther out, braziers and lanterns glow around the banks to indicate actors waiting for their entrances.

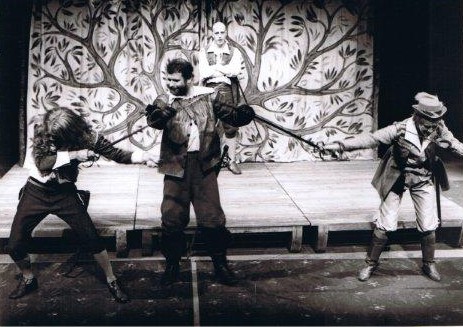

Most of the acting takes place on the little stage, as if by an Elizabethan touring company. Now and then it overflows. The sea-coast of Illyria is on the carpet, and so are Sir Andrew’s hilarious duels with the twins. Sometimes an actor comes right downstage for a confidence, and then the dim figures from the outskirts creep forward to light him or her with their lanterns. A joke clock representing the whirligig of time – a great propeller with the sun and moon at opposite ends – is occasionally wheeled forward to indicate some specific hour. Malvolio’s dark room is just a little box-like cage with just enough room for him to lie down. It is all enchantingly picturesque.

This is not an occasion for great performances; it is particularly a director’s work of art. Lines are spoken with no more awareness of poetry than if they were chat between the Illyrian Sloane Rangers. This does not deprive them of poetry (and anyway, most of the play is in prose). Exceptional care is taken to ensure that the precise sense of every phrase is expressed, so that when poetry is implicit, it emerges naturally, and the jokes sound funnier and more plentiful than ever before in my experience.

Mr. Trotter throws in some jokes of his own. Sir Toby, Sir Andrew and Fabian, unable to see enough of Malvolio reading his fake letter by peeping over the back-cloth, improvise instant seats on the curtain-rail, dangling puppet legs in front of them. During the interval, mulled wine is sold from the stage.

Karen Gledhill’s Viola really looks at first entrance as if she has just been dragged out of the sea and having become Cesario, she is naturally boyish and funny.

Mike Burnside is Sir Toby, well-bred and never excessively drunk, and Patrick Romer is Sir Andrew, never excessively foolish, except at fencing. Malvolio, wearing a trim courtier’s beard, is a handsome figure as Edmund Kente presents him, so all the more pitiful in his subsequent break-down.

I have a way of recommending people to make this considerable trip to Exeter to see productions at the Northcott, and I make no secret of my special admiration for Mr. Trotter’s work. I must now repeat it. This Twelfth Night is worth any journey. It still has three weeks to go, and there is not likely to be anything more colourful, comic or affecting this side of Christmas, or indeed months after.