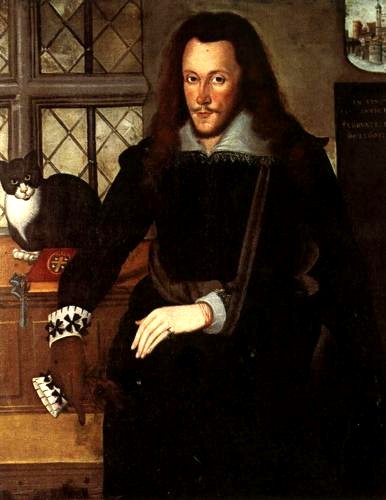

In Boughton House (the Northamptonshire home of the Duke of Buccleuch) there hangs a painting of Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron and lover.

He is shown as a prisoner in the Tower of London – accompanied by a black and white cat.

The Earl of Southampton’s presence in the Tower is easily explained.

On 8 February, 1601, along with his intimate friend, Sir Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex (and two hundred of their hot-headed followers) Southampton had rebelled against Queen Elizabeth.

The men wanted Elizabeth to name King James VI of Scotland as her successor. They feared that, if she did not, civil war would break out when she died.

The Queen, for her part, feared that, if she did name James as her successor, she would be assassinated. She had, after all, executed King James’s mother, Mary Queen of Scots.

Another aim of the rebellion was to kill Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Robert Cecil who had plotted against Essex while he was away from the Court, fighting in Ireland.

But the attempt (after divine service on a Sunday morning) to raise the citizens of London had fallen flat. Everyone had prospered too well under Elizabeth.

Essex was beheaded and Southampton imprisoned in the Tower. Southampton had also been sentenced to death, but his mother and his wife had pleaded for mercy. Queen Elizabeth agreed to transmute the death sentence to life imprisonment.

She despised the long-haired, quarrelsome Southampton, but realised he was no real threat to her. Also, the beheading of Essex had proved very unpopular with her subjects. The London mob had tried to lynch Essex’s executioner who had taken three blows to sever his head.

The Cat in the Tower is more difficult to explain.

A legend has grown up, first reported in 1793 by Thomas Pennant in Some Account of London:

After he [the third Earl of Southampton] had been confined there [the Tower] a small time, he was surprised by a visit from his favourite cat, which had found its way to the Tower; and, as tradition says, reached its master by descending the chimney of his apartment. I have seen at Bulstrode, the summer residence of the late Duchess of Portland, an original portrait of this Earl, in the place of his confinement, in a black dress and cloak, with the faithful animal sitting by him.

Pennant, at least, has the good grace to add:

Perhaps this picture might have been the foundation of the tale.

Even the great Southampton scholar, C.C. Stopes (mother of Marie) joins in the cat speculation by suggesting that Southampton’s wife brought the cat with her on a ‘prison visit’ to her husband ‘to help to comfort, and to help calm the excitement of meeting again after such a long and anxious separation.’

In our time, Southampton’s ‘favourite cat’ has even acquired a name:

‘TRIXIE’

To celebrate its 2,000th view, The Shakespeare Code has sworn to eliminate Trixie the Cat with EXTREME PREJUDICE.

●

The third Earl of Southampton, stripped (officially, at least) of his title and signing himself plain ‘H. Wriothesley’, was incarcerated on 8 February, 1601. He was ill from the start of his imprisonment and on 22 March the Privy Council allowed a doctor in to treat his ‘quartern ague’ which produced ‘swelling in his legs and other parts’.

In August the following year (1602) the Lieutenant of the Tower transferred the ‘weak and very sickly’ Southampton to a more salubrious lodging, but warned the Privy Council that:

Without some exercise, and more air than is convenient for me to allow without knowledge from your honours of her Majesty’s pleasure, I do much doubt of his recovery.

Southampton’s mother, Mary, was allowed in to see him later that month, then, in October, his wife, Elizabeth.

In February of the following year (1603) the Jesuit Father Rivers noted that: ‘

The Earl of Southampton in the Tower is newly recovered of a dangerous disease…but in no hope of liberty.

Then, on 24 March, 1603, Queen Elizabeth died.

James became King of England as well as King of Scotland and everything turned round. The traitors of Elizabeth’s reign became the heroes of James’s.

●

When Southampton heard that Elizabeth had died, he threw his hat, for sheer joy, over the walls of the Tower. He expected King James would release him and pardon him.

He also hoped James would make him his lover.

However, many other handsome young aristocrats (including the Countess of Pembroke’s two sons) were vying for this powerful position.

How could Southampton, imprisoned in the Tower, catch the King’s eye before his rivals?

He could commission a portrait and rush it to King James in Scotland!

●

The painting is heavily coded:

- The book on the window ledge (gilt-edged and most likely a Bible) has the Southampton family crest of four silver falcons embossed on the cover. This shows the painting was executed after Southampton’s title was restored by the House of Peers on 26 March, 1603.

- Southampton is dressed in black with a ring prominently displayed on his left finger. He is in mourning (in a ‘suit of woe’) for his friend, the second Earl of Essex who, in James’s eyes at least, was a ‘martyr’. The ring is a memorial tribute to Essex.

- A pane of glass in the window is smashed. This symbolises the violent, untimely death of the youthful Essex.

- Southampton’s arm is in a sling. This shows that Southampton is still recovering from his illness and so needs freedom and fresh air. It also allows Southampton (a) to show off the beauty of his long, elegant fingers and (b) offer his ‘submissive’ left hand to James as a lover.

- Red threads (holding tiny red gemstones) are wrapped round Southampton’s wrist. This indicates (a) that Southampton was recovering from a form of rheumatism (red thread round the wrist was an old folk-remedy) and (b) that Southampton was offering his love to James (red gems were all named ‘rubies’ at the time and symbolised passion).

- Southampton’s hair cascades, unadorned, round his shoulders. This shows (a) the unaffected truth and straightforwardness of his nature, (b) his hatless deference to the new King into whose presence the portrait would be taken and (c) his readiness to symbolically ‘wed’ James. Brides at this period wore their hair, plainly brushed, down to their shoulders for the wedding ceremony.

[See the painting (also now at Boughton House) of the Earl of Southampton’s bride, Elizabeth Vernon, combing her shoulder-length hair in preparation for the wedding service which will make her a Countess]

7. There is a painting (within the painting) of the Tower of London with four white swans swimming in its moat. These swans represent the faithful lovers who will greet Southampton when he is released from the Tower.

8. Beneath the painting of the Tower is the exact date of Southampton’s incarceration, ‘FEBRUA: 8 1600:’ (The New Year at this time, started on 31 March). This date is followed by: ‘601: 602: 603: APRI:’

There is no exact date after ‘APRI’ as there is after ‘FEBRUA’. If the painting had been executed after the Earl of Southampton’s release, the exact date would have been included.

This painting, the Shakespeare Code believes, is an invitation to King James to fill in the exact date in April by ordering Southampton’s release from the Tower.

The painting was a rushed job, executed over six days and nights (26 March to 1 April) then sent, by horseback courier, to James at Holyrood House in Edinburgh.

King James, smitten with the painting of the Earl, responded on 5 April with a letter to the ‘Peers, Nobility and Council’ of England:

Although we are now resolved, as well in regard of the great and honest affection borne unto us by the Earl of Southampton as in respect of his good parts enabling him for the service of us, and the state, to extend our grace and favour towards him….we have thought meet to give you notice of our pleasure….which is only this : Because the place is unwholesome and dolorous to him to whose body and mind we would give present comfort, intending unto him much further grace and favour, we have written to the Lieutenant of the Tower to deliver him out of prison presently to go to any such place as he shall choose in or near our city of London, there to carry himself in such quiet and honest form as we know he will think meet in his own discretion, until the body of our state, now assembled, shall come unto us, at which time we are pleased he shall also come to our presence, for that as it is on us that his only hope dependeth, so we will reserve those works of further favours until the time he be-holdeth our own eyes, whereof as we know the comfort will be great unto him so it will be contentment to us to have opportunity to declare our estimation of him…

The painting had clearly worked at every possible level.

But what is ‘Trixie’ doing in the Tower? And why is she staring out of the painting?

For the answer to this question, we must turn to….

The Swan of Avon….

William Shakespeare….

(it’s best to read Part Two now.)