(It is best to read The Introduction first)

The French Connection.

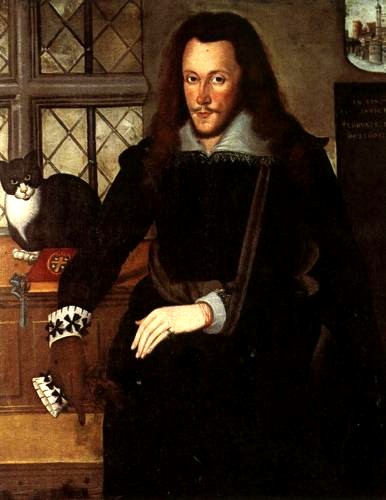

The Earl of Essex was certainly not invited to the new vesion of What You Will ( Twelfth Night) played before Queen Elizabeth on Twelfth Night in 1601. Her former lover was sick, impoverished and in disgrace…

He had returned from leading the Irish Campaign without the Queen’s permission, and had burst into her morning chamber before she had time to put on her make-up and wig…

Essex’s many enemies at Court, especially Sir Walter Raleigh (‘The Fox’) and Sir Robert Cecil (‘The Ape’) had used this incident to poison the Queen’s mind against her favourite. She took away his ‘farm’ on sweet wines, his main source of income, and refused to see him.

Essex’s entourage was split as to what to do next.

Half favoured rebellion:

Stir up the citizens of London, march on Whitehall, kill Cecil and Raleigh and force the Queen to name King James VI of Scotland as her successor!!!

Half favoured appeaesment:

Fall on your knees, lads, and beg Elizabeth’s forgiveness…

William Shakespeare favoured appeasement. He knew his life was in danger. His play, The Life and Death of King Richard II – a coded attack on Elizabeth’s waywardness and favouritism – was being played as a piece of ‘agit-prop’ in the streets and houses of London.

If Essex, as an aristocrat, were to have his head cut off, there was a good chance Shakespeare, as a commoner, would be hanged, drawn and quartered.

With the re-hashing of What You Will (more frocks! more dancing!) came the chance for flattery…

Her Majesty’s guest, Don Virginio Orsino, Duke of Bracciano, was ‘honoured’ by having the leading character, Orsino (sexy, handsome, powerful) named after him.

The Shakespeare Code believes that Elizabeth was also ‘honoured’ by having the character Olivia, (sexy, beautiful, powerful) embody all of the Queen’s very best aspects…

When Viola says to Olivia…

I bring no overture of war, no taxation of homage; I hold the olive in my hand: my words are full of peace as matter…

….it is Shakespeare addressing Elizabeth herself .

When Shakespeare re-creates Olivia, he paints a portrait of her bravery, self-control, femininity, vulnerability and sense of fun.

Twenty years previously, Catherine de’ Medici had suggested a marriage between her son, the Duc d’Alencon and the much older Queen Elizabeth. The dashing Jean de Simier….

a choice courtier, a man thoroughly versed in love-fancies, pleasant conceits and court dalliances…

….was sent to plead Alencon’s love-cause, and Elizabeth had fallen head over heels in love with him. As Edmund Bohun wrote…

The Queen danced often then, and omitted no sort of recreation, pleasant conversation, or variety of delights for his [Simier’s] satisfaction: at the same time the plenty of good dishes, pleasant wines, fragrant ointments and perfumes, dances and masques, and variety of rich attires, were all taken up, and used, to show him how much he was honoured..

Elizabeth was even rumoured to be secretly sleeping with her ‘Monkey’ in the bedroom of one of her Ladies-in-Waiting….

‘The Bear’ (Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth’s old lover) became so jealous of Simier he claimed the Frenchman was using magic and love-potions on the forty-five year old Queen. He even tried to assassinate him..

When Alencon himself arrived things got even worse….or better!

One day the Queen greeted her five-foot high, pock-marked, but very sexy ‘Frog’, at the door of her own bedchamber, dressed only in a nightgown…

A three-hour ‘private audience’ ensued.

After which she gave the Frog a ring….

In Twelfth Night, the love-sick Orsino sends his page, ‘Caesario’ (Viola dressed as a boy) t0 plead his love-cause to Olivia, just as the Monkey had pleaded for the Frog to Queen Elizabeth…

And Olivia gives ‘Caesario’ a ring as a love token, just as Elizabeth gave one to the Frog…

But, again just like Olivia in the play, Elizabeth did not want to ‘match above her degree’.

So, like ‘Caesario’s’ supposed ‘dead sister’ in the play, Queen Elizabeth…

never told her love,

But let concealment like a worm i’ th’ bud

Feed on her damask cheek; she pin’d in thought,

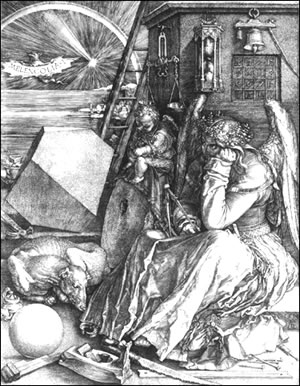

And with a green and yellow melancholy

She sat like Patience on a monumnet,

Smiling at grief….

After Alencon’s departure in 1582, the Queen expressed identical feelings in an identical way in a beautiful poem she wrote…

I grieve and do not show my discontent;

I love, and yet am forced to seem to hate;

I do, yet dare not say I ever meant;

I seem stark mute, but inwardly do prate.

I am and not; I freeze and yet am burned,

Since from myself, another self I turned.

My care is like my shadow in the Sun –

Follows me flying, flies when I pursue it,

Stands, and lies by me, doth what I have done;

His too familiar care doth make me rue it.

No means I find to rid him from my breast,

Till by the end of things it be suppressed.

Some gentler passion slide into my mind,

For I am soft and made of melting snow;

Or be more cruel love, and so be kind.

Let me or float or sink, be high or low;

Or let me live with some more sweet content,

Or die, and so forget what love e’er meant

When, two years later, Elizabeth learnt that Alencon had died, she dressed in black and wept openly for three weeks. Each year she commemorated the day of his death.

Twelfth Night celebrates this ‘gentle’ quality in the Queen….

As ‘Caesario’ says of Olivia (and herself):

How easy is it for the proper false

In women’s waxen forms to set their hearts!

Alas, our frailty is the cause, not we,

For such as we are made of, such we be…

This version of the play empathises completely with the pressures on Olivia. She was not born to Stewardship and has to take over the running of the household after the deaths of her dearly beloved father and brother.

Similarly, Elizabeth was not born to be Queen. She only took over the running of England after the deaths of her own dearly beloved father and brother, Kings Henry VIII and Edward VI. (And Bloody Mary, of course. But she’s the monarch nobody mentioned….)

Olivia, one of Orsino’s servants tells us…

will veiled walk

And water once a day her chamber round

With eye-offending brine…

just as Elizabeth did after the death of Alencon….

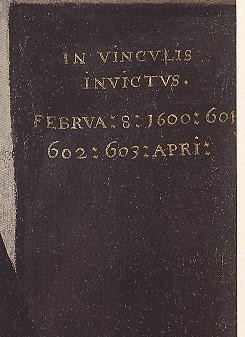

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Shakespeare Code has discovered that the great Canadian researcher, scholar, Quaker and First World War pacifist (though he fought in the Second) Dr. Leslie Hotson, takes exactly this view of Olivia in his ground-breaking, 1954 book, The First Night of Twelfth Night.

He even quotes the same poem by Queen Elizabeth…

The Code is always delighted to acknowledge pre-emption.

Especially from a Cambridge man.

(Hotson was a Fellow of King’s College from 1954-60).

It’s best to read Part Two now.

And: Viola’s ‘Willow Cabin’ speech Decoded.