Trix at the Flix!

Brothers and Sisters of the Shakespeare Code….

Let Your Cat say right away that Hamnet’s heart is in the right place. The film attempts to relate William Shakespeare’s life to his work.

‘But that’s the most obvious thing to do!’ Your Cat hears you cry. But believe me it’s not. When our Chief Agent, Stewart Trotter, was studying English at Cambridge – some time in the last century – students were forbidden to draw on a writer’s life when analysing his work.

This was called the New Criticism – and right in its centre was T. S. Eliot.

He knew he’d behaved badly in his private life – and in his politics he was borderline Fascist. His fear was that when people found out what he was like, they would reject his poetry. So he put it about that the quality of a man’s verse had nothing to do with the quality of the man himself.

Hamnet shows how Shakespeare – a man violent and autistic – poured out his grief for his son when he died by writing Hamlet. His wife – Agnes in this version rather than Anne – divines that her husband can only be fulfilled by leaving their village – Stratford-upon-Avon – and going to London. Husband and wife are two of a kind – wild, original loners who can only fit in with each other…

As I’ve said, the film’s heart is in the right place. It’s its brain that is the problem.

It hasn’t got one….

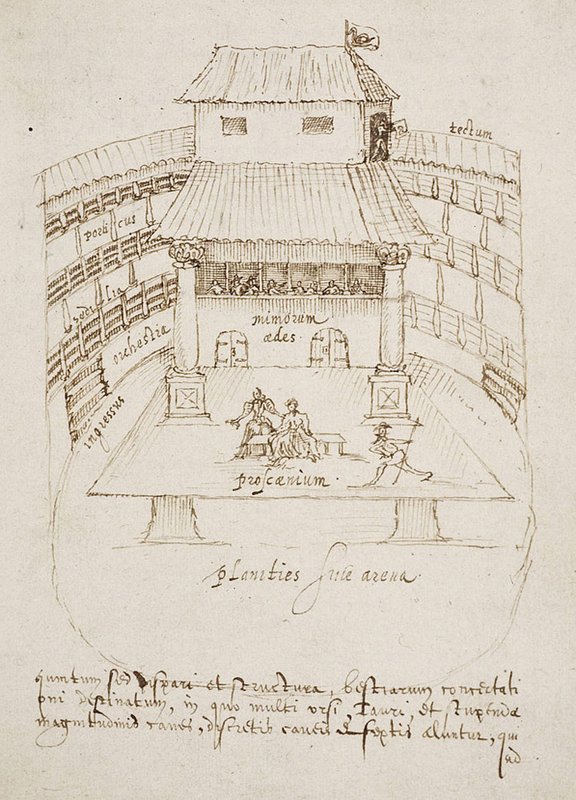

There is a huge problem with the central idea. An early version of Hamlet was already in existence when Hamnet died, aged 11, in 1596 – and there is a strong possibilty that Will was actually playing the Ghost in the Paris Gardens at the time of his son’s death.

The film also ignores Nicholas Rowe – Will’s first biographer in 1709 – who says he fled from Stratford because he was caught poaching deer belonging to Sir Thomas Lucy – and then writing an obscene ballad about him which he hung on Lucy’s park gates.

The film is also highly questionable in its presentation of Will’s father, John, as a violent, debt-ridden, alcoholic. In reality he was at one time the Bailiff of Stratford-upon-Avon, so successful as a glover that he actually lent money to the Council. He even paid off the debts of Anne Hathaway’s father who – despite what the film says – was a close friend. John was also an ardent, committed, Roman Catholic who risked imprisonment or even death by putting his mark on a Testament of Faith. He did at one point have debts, but that was because the Earl of Leicester moved near Stratford when Will was a teenager – and proceeded to harass and ruin followers of the Old Faith. Sir Thomas Lucy was his agent…

So how did Will process his grief? And did it feature in other works by him?

The clue, strangely, is in the film itself. At one point Sussana, Will’s older daughter, reads a poem to her sister Judith her father has written about her mother. He describes how even beautiful people have to die along with everything else in Nature.

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silver’d ore with white:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And Summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard:

[When I witness the ticking of a clock, the transformation of day into

night, a fading violet, trees bereft of leaves that once gave shade to cattle

and the green corn transformed into sheathes with white beards like old

men…]

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do them-selves forsake,

And die as fast as they see others grow

[Then I question the very nature of your beauty, as it will be subject to

time and decay. All beautiful things depart from their original natures and

fade as quickly as they see other beautiful things come into being.]

What the film doesn’t give us is the conclusion:

And nothing ’gainst Time’s scythe can make defense

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

Will is saying the only solution is to have children you can leave behind.

But Anne already has children – so what is this all about?

The fact is that this poem is a Sonnet. Not only is it a Sonnet, but it was written to a young man – to be precise, the seventeen year old Harry, Third Earl of Southampton – Will’s long-term patron and lover.

Harry’s mother had commissioned Will to write seventeen Sonnets for his seventeenth birthday, urging him to get married and have a son.

He was Will’s true love – and though John Aubrey tells us Will spent his summers with his family at Stratford, we know from his Sonnets that all Will could think about was Harry. Summer without him was Winter.

[The poem that follows is Sonnet 97 in the sequence published in 1609. In his upcoming book, Shakespeare’s Sonnets Decoded, Stewart has re-arranged the sequence in chronological order – and this becomes Sonnet 61. The ‘translations’ in square brackets are posted by permission of Magic Flute Publishing.]

How like a Winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

What freezings have I felt, what dark days seen?

What old December’s bareness every where?

[My absence from you has been like winter. You are like the most

pleasant part of the year. I have felt cold, the days have been dark and the

natural world is stripped of its colour.]

And yet this time remov’d was summer’s time,

The teeming Autumn big with rich increase,

Bearing the wanton burthen of the prime,

Like widowed wombs after their Lords’ decease.

[In reality it was the summer time and the abundant autumn – full of

the fruits of the spring – was like a pregnant widow with her womb swollen

with the offspring of her dead husband.]

Yet this abundant issue seem’d to me

But hope of Orphans, and un-fathered fruit;

For Summer and his pleasures wait on thee,

And thou away, the very birds are mute.

[But the abundant produce of the spring seems to resemble the

hopelessness of an orphan without his or her father, or infertile fruit

because the Summer is your servant. When you are away, even the birds

stop singing.]

Or, if they sing, ’tis with so dull a cheer,

That leaves look pale, dreading the Winter’s near.

[And even if they do sing, it is with total lack of joy as if they are

dreading the approach of winter.]

Shakespeare was so obsessed with the handsome young aristocrat he hardly noticed his family at all. And when he wasn’t writting Sonnets to him he was writing long narrative poems for him instead.

So how did Shakespeare cope with his grief if he didn’t write Hamlet ?

He coped with it by turning Harry, Earl of Southampton, into a replacement son….

Sonnet 127 New Order. Sonnet 37 Old Order.

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth,

So I, made lame by Fortune’s dearest spite,

Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth.

[As an infirm, old father takes pleasure in seeing his son engage in

youthful, athletic activities, so I, having suffered the worst that fate can do

to a man, to have his son taken away from him by death, I now delight in

your moral worth and honesty.]

For whether beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit,

Or any of these all, or all, or more

Intitled in thy parts do crowned sit,

I make my love engrafted, to this store:

[I do not know which is your crowning glory – your good looks, your

aristocratic birth, your wealth or your intelligence. Perhaps it’s one of

these, or all of them or others that I don’t know about. Whatever the truth,

I intend to join with these qualities for all time, the way we graft one plant

onto another.]

So then I am not lame, poor, nor despise’d,

Whilst that this shadow doth such substance give

That I in thy abundance am suffic’d,

And by a part of all thy glory live:

[This stops me being wounded by the grief for my son, or impoverished

or unappreciated while this act of imagination gives such substantial

benefits. I am nurtured by the multiplicity of your gifts and bask in your

glory.]

Look what is best, that best I wish in thee;

This wish I have, then ten times happy me.

[Whatever is best, I wish it for you. As it belongs to you – and you

belong to me – I am overwhelmed with happiness.]

Will in the next few Sonnets becomes obsessed with death – and imagines how his death will effect Harry – with no consideration how Hamnet’s death has affected his wife. He even counsels Harry to forget all about him.

But his grief also turns to violence….

Leslie Hotson – the brilliant Canadian literary historian and sleuth

– discovered in 1931 that in November, 1596 Will was up before the

Magistrates and bound over to keep the peace.

In November, 1596, William Wayte petitioned ‘ob metum mortis’ (for

fear of death) in a suit for sureties of the peace against William Shakespeare,

Francis Langley, Dorothy Soer, wife of John Soer and Anne Lee. Will also

figures in a retaliatory law-suit on the side of Langley.

We don’t know for certain who the women were, but there were most

likely prostitutes and Langley, who owned the Swan Theatre and tenements

in the area, was a known crook and moneylender.

Will, in mixing with low life and prostitutes in the Paris Gardens, was

behaving again like his new creation, Falstaff.

Because of the ‘shame’ of Will’s Court Appearance, Harry dropped Will for a bit.

Will feared that this rejection might one day become a permanent one

– as it was for Falstaff.

Sonnet 136. (36)

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one:

So shall those blots that do with me remain,

Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

[I have to acknowledge that we have to live apart till the scandal of my

court appearance blows over – although we still love one another as though

we were one person. So all the shame will be borne by me, without any help from you.]

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite,

Which though it alter not love’s sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love’s delight.

[Though we are two separate men, we are lovers and look at life the

same way – even if circumstances at the moment force us to be apart. This

won’t interfere with our love for each other, but it steals time away from us

which we could have enjoyed together.]

I may not ever-more acknowledge thee,

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

[I cannot acknowledge you as my provider and patron because my

appearance in the Magistrates’ Court would bring shame to your family

name. And you can’t show me favour in public without detracting from

the family honour.]

But do not so; I love thee in such sort

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

[Don’t honour me publicly. I love you in such a way that you are in

fact myself and I can be honoured in your honour.]

In his new book, Shakespeare’s Sonnets Decoded, Stewart argues that Shakespeare did mourn for his son and his grief did affect his plays….

But this was almost a decade later – and happened in an extraordinary and violent way.

Your Cat will reveal all in her next post….

‘Bye now….

Leave a comment