Shakespeare’s Links with the Church of St. Giles’ Without Cripplegate.

Fr. Jack Noble, the Rector of St. Giles’ without Cripplegate, invited Stewart Trotter to give a talk to the congregation on Sunday, 1st September, 2024.

Here is the transcipt.

XXX

William Shakespeare had two certain links with St. Giles’ Without Cripplegate.

From around 1604 he lodged with an immigrant family in a house on the corner of Silver Street and Muggle Street – near the Church but within the City Walls and in a different parish.

The two streets have since become part of the London Wall Car Park.

We also know that Shakespeare’s baby nephew, Edward – son of Shakespeare’s brother Edmund – was buried in the Churchyard of St. Giles on 12th August 1607.

But in the 1870s a Roman Catholic priest, Richard Simpson, suggested a much earlier, deeper, link with St. Giles’ that I should like to develop in this talk.

But first, and I have Father Jack’s permission to do so, I’d like to question some statements about Shakespeare on the Church’s website. To be honest I did this sometime in the last century – when the Church had leaflets rather than websites. No-one took any notice, so I’m here for a second go.

The Church website reads:

It is said that Shakespeare had to escape from Stratford-upon-Avon because he was going to be prosecuted for stealing deer from Charlecote Park, owned by Sir Thomas Lucy. Shakespeare fled to Cripplegate to stay with his brother, Edmund – and if he had attended St Giles’ he would have bumped into the Lucy family, as it was their parish church! Edmund, who was an actor like his brother and who is buried in Southwark Cathedral, had two sons who were baptised in St Giles’, and tradition has it that William Shakespeare acted as the chief witness.

It would have been difficult for Shakespeare to have stayed with his brother Edmund as he was only two at the time and living in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Edmund only had one son, Edward, who was certainly buried in the St. Giles’ churchyard, but was baptised at St. Leonard’s, Shoreditch – more than a mile away – on 12th July 1607.

The St. Giles’ clerk can’t have known Edmund very well because he mixes up his name with his baby’s name – but he does give gives us the information that Edmund was a ‘player’ and that his little son was ‘base born’ – that is, illegitimate.

It is unlikely at this time that Shakespeare attended services here. He was a mendacious Roman Catholic in league with a plotting Jesuit. At least that was the view of a parishioners of St. Giles’ who is buried in the church and has a monument on the south wall: the eminent historian and cartographer, John Speed.

He published his attack on Shakespeare in his ‘History of Britian’ in 1611 – when Shakespeare was still alive, at the height of his fame and was probably living round the corner.

But the laws of libel were draconian: in 1579 Queen Elizabeth had the right hand of a writer – who had dared criticise her wooing of Anjou – chopped off with a cleaver. He went under the unfortunate name of John Stubb.

So Speed couldn’t name Shakespeare directly. Instead, he referred to his plays.

When Shakespeare first created ‘the fat knight’, Falstaff, he gave him a different name – Sir John Oldcastle. Oldcastle had really existed – a Lollard who had been hanged for dissent at the beginning of the fifteenth century. He was revered by Protestants as a hero and martyr – but Shakespeare lampooned him as a scapegrace, a drunk and a thief.

Robert Persons – the radical Jesuit – followed suit.

He described Oldcastle as ‘a ruffian, a robber and a rebel.’

Speed attacks Persons and Shakespeare as ‘this papist and his poet, of like conscience for lies, the one ever feigning and the other ever falsifying the truth’.

‘Papist’ even in 1611 was a term of abuse – and in 1655 Thomas Fuller, an Anglican priest and historian, tells exactly the same story.

He writes about ‘malicious papists’ and ‘petulant poets’.

But we have to wait till 1688 for a direct statement Shakespeare was a Roman Catholic. Another Anglican priest and historian, called Richard Davies inherited the papers of yet another Anglican priest and historian, William Fullman, who claimed that Shakespeare ‘Died a papist’.

Certainly Shakespeare’s early years follow a Roman Catholic profile. His father John – as well as a glover, wool-dealer and butcher – was also the Bailiff of Stratford-upon-Avon – so rich he actually lent money to the council. But when his son Will entered his teens, Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester – Queen Elizabeth’s favourite and lover – came to live at nearby Kenilworth Castle.

He began to harass Roman Catholics – forcing their attendance at Anglican church and raising their rents, sometimes ten times over.

Leicester was aided and abetted in Warwickshire by his ruthless Protestant agent, Sir Thomas Lucy….

……so rich and powerful he was able to entertain Queen Elizabeth at his new mansion at Charlecote.

John Shakespeare clung to the Old Faith, so Leicester ruined his business. John became so poor he had to remove Will from school to help work in the shop.

But a Catholic support network was forming. John Cottam – a Lancashire Catholic – became the Stratford schoolmaster. He was a friend, neighbour and tenant of the Roman Catholic Hoghton family – and there is a tradition – and even documentary evidence – that the teenage Shakespeare became a children’s tutor and entertainer at Hoghton Hall.

But Hoghton Hall was raided by Leicester’s soldiers and Will had to return home. He fell in love with family friend, Anne Hathaway……

……..wooed her with ballads, got her pregnant and married her.

Just at this time Leicester and Lucy arrested Edward Arden – a distant, aristocratic cousin of Will’s mother.

They accused him of harbouring a Catholic priest in his household and plotting against the Queen. He was found guilty of treason and hanged drawn and quartered. In what could well have been a Roman Catholic revenge, Will poached Sir Thomas Lucy’s deer – then hung a libellous poem about him on the gates of Charlecote.

The refrain was: ‘Lucy is lousy’.

Nicholas Rowe……

……in his 1709 biography of Shakespeare, the first ever written – gives his version of this story:

In this kind of settlement Shakespeare continued for some time, till an extravagance that he was guilty of, forced him both out of his country and his way of living which he had taken up, and though it seemed at first to be a blemish on his good manners, and a misfortune to him, yet it afterwards happily proved the occasion of exerting one of the greatest Genius’s that ever was known in dramatic poetry.

He had by a misfortune common enough to young fellows, fallen into ill company; and amongst them, some that made a frequent practice of deer-stealing, engaged with them more than once in robbing a park that belonged to Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford.

For this he was prosecuted by that Gentleman, as he thought, somewhat too severely; and in order to revenge that ill usage, he made a ballad upon him.

And though this, probably the first essay of his poetry, be lost, yet it is said to have been so very bitter, that it redoubled the prosecution against him to that degree, that he was obliged to leave his business and family in Warwickshire, for some time, and shelter himself in London.

Here the story hits a brick wall. Edmond Malone……

……an Irish lawyer writing at the end of the eighteenth century – dismissed Rowe’s biography as rubbish – and, though Malone had no story to put in its place, scholars have followed him ever since.

They have, literally, lost the plot.

BUT – Rowe was working on information he got from Thomas Betterton……..

…..an actor obsessed with Shakespeare who was the first to do field-work in Stratford-upon-Avon. He had worked with Sir William Davenant…….

……Shakespeare’s godson, who himself got his information from ‘old Mr Lowen’ who had been directed by Shakespeare. So Rowe’s biography has a provenance that goes right back to the Bard himself.

And the deer-poaching story has three other sources that pre-date Rowe – one of which is William Fullman – the same Fullman that wrote Shakespeare ‘died a Papist’. He says that ‘Shakespeare was much given to all unluckiness in stealing venison and rabbits, particularly from Sir Blank Lucy who oft had him whipped and sometimes imprisoned and at last made him fly his native country to his great advancement’.

The fact that Fullman doesn’t know Lucy’s Christian name makes the story ring all the more true. And if it IS true, Shakespeare was in considerable danger. Poaching deer led to at least three months in prison, a fine of three times the cost of the deer and sureties for seven more years. And as we have seen, the libel laws were even more terrifying.

Shakespeare had to get out of town.

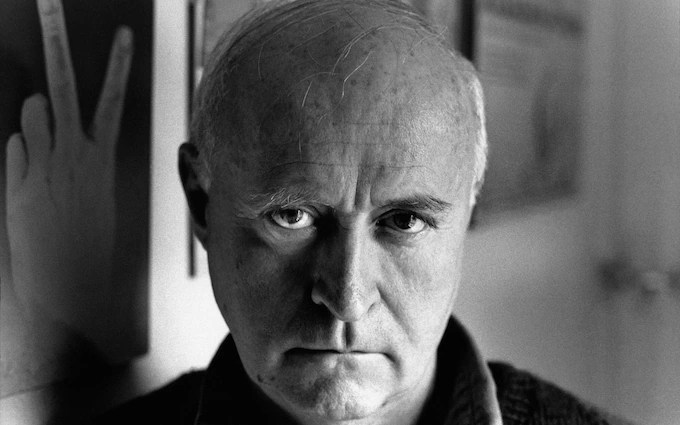

After 1688 there is no mention of Shakespeare’s Roman Catholicism for nearly two hundred years. But then Richard Simpson came along. Educated at the heavily Anglo-Catholic Oriel College – and ordained as an Anglican priest in 1844 – he married a rich cousin and then, in 1846, went over to Rome. He was therefore no longer able to be a priest – but he became a Shakespeare scholar instead – earning praise from Matthew Arnold and William Gladstone.

He was the first person in modern times to assert that Shakespeare was a Roman Catholic.

And this is where St. Giles’ comes into its own. Simpson studied the pamphlets, poems and plays of the so-called ‘University Wits’ – contemporaries of Shakespeare but graduates from Oxford and Cambridge – Robert Greene…..

and Thomas Nashe….

Simpson found coded attacks on both Shakespeare and playwright Thomas Kyd. The Wits dismissed them as ‘grammarians’ – that is, grammar school boys with delusions of grandeur.

Kyd came from a Catholic family like Shakespeare – and it could well be that the Catholic network put them together. Greene and Nashe reveal that they were both ‘noverints’ – that is, lawyers’ clerks – who worked and lived in the City of Westminster – but would collaborate by candlelight at night and then starch their beards and take a walk down the Strand to the City of London to ‘turn over French dowdie’ – that is, get up to no good – as Shakespeare’s young brother, Edmund, was clearly later to do….

But, intriguingly, Nashe describes how Kyd and Shakespeare would ‘shrift to the vicar of S. Fooles, who instead of a worser be such a Gothamist’s ghostly father’. People from the town of Gotham were famously stupid..

And Greene writes how Kyd and Shakespeare ‘cannot write true English without the help of clerks of Parish churches.’

Greene goes on to complain that Kyd and Shakespeare wrote plays that ‘abuse scripture’ by drawing on sentiments and whole phrases from the Bible – and quote examples of this from a play called ‘The Fair Em’ – first performed by Lord Strange’s Men……

………and attributed by King Charles II’s librarian to William Shakespeare.

It has resemblances to ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’. The lovers overhear their rivals reciting their love verse – and there is a part similar to Berowne – the plain-speaking Valingford, who falls in love with the Miller’s daughter, the Fair Em of the title – and stays true to her even though she feigns blindness to test his love. A perfect part for Shakespeare.

The play also has a low life character who lusts after Em, carries a chamber pot with him and threatens to break wind.

His name is Trotter.

The play was performed in the City of London – but has references, some of them topical, to Manchester, Lancashire and Cheshire.

Lord Strange was made Mayor of Liverpool in 1585, Alderman of Cheshire in 1587 and Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1588 – so the play most probably toured the Midlands first.

Simpson believed that Shakespeare wrote ‘The Fair Em’ – as do some modern scholars – but others think it was Kyd. Kyd later became employed by Lord Strange – so my own belief is that ‘The Fair Em’ – which has a double plot – was a collaboration between the two men.

Greene finally spikes the identity of the ‘vicar of Saint Fooles’ and ‘the clerks of parish churches’ by writing:

In charity be it be spoken I am persuaded that the sexton of St. Giles without Cripplegate would have been ashamed of such blasphemous rhetoric.

This leads Simpson to hint in an index that the vicar of St. Fooles was the vicar of St. Giles, the Rev Robert Crowley – who was also a printer and poet and who was buried in the chancel of this church.

But I would like to suggest another priest was involved: John Foxe…..

………the author of ‘Acts and Monuments’, better known as ‘Foxe’s Book of Martyrs’ – who was also buried in the chancel, next to Crowley and under the same stone.

Crowley and Foxe were a double act from the start. They were both born in the Midlands around 1516 to 1519 in the reign of King Henry VIII. In the 1540s they became scholars at the fiercely Catholic Magdalen College, Oxford – where both men secretly converted to Protestantism. The authorities, becoming suspicious, spied on both men. Foxe said it was like being in prison.

The crunch came when – to continue as Fellows at the college – both men had to be ordained. Foxe described this proposed celibacy as ‘castration’.

Both men fled Oxford and became tutors to Protestant families – Crowley to the children of Sir Nicholas Poyntz at Iron Acton in Gloucestershire – and Foxe to the fourteen year old Thomas Lucy at Charlecote in Warwickshire.

Foxe ruled himself out of the priesthood – for the time being at least – by getting married.

In 1547 King Henry died………

King Edward succeeded him at the age of nine……..

…………..and England became a Protestant Country. Both Crowley and Foxe made their way to London.

Crowley started to write – and he had a lot to write about. By dissolving the monasteries, King Henry had ended one form of corruption – but had opened the door to another. It lead to a Protestant scramble for wealth and power – and the complete neglect of the poor and the sick who had been looked after by the monks.

Crowley and Foxe were no proto-Marxists. They hated Robert Kett’s rebellion in Norfolk in 1549.

They believed that the rich man was in his castle and the poor man at his gate because God had put them there. But what could be done about poverty and starvation?

Crowley and Foxe – along with other so-called ‘common wealth’ writers – came to the conclusion that the rich must re-distribute their wealth – and do so voluntarily.

Crowley furiously attacked all those ‘possessioners’—especially ‘engrossers of farms, rack-renters, enclosers, leasemongers, usurers and owners of tithes’—who failed to practise good stewardship. But to give charity a helping hand, Crowley and Foxe petitioned Parliament to change the law – and threatened the greedy rich with the torments of hell.

Crowley set up a printing press in Ely Rents, Holborn – and was the first university man to become a printer and publisher. Both Crowley and Foxe were evangelicals as well as puritans. Their dream was to popularise Protestant Christianity and make it accessible to everybody.

Crowley wrote a volume of epigrams – which attacked drunkenness – while admitting that Curates often drank more than their parishioners – attacked bear-baiting – ‘a full ugly sight’ – and even attacked bowling alleys.

But, most interesting of all, the epigrams attacked women who dyed their hair and used make-up:

Let thine apparel be honest;

Be not decked past thy degree

Neither let thou thine head be dressed

Otherwise than beseemeth thee.

Let thine hair bear the same colour

That nature gave it to endure;

Lay it not out as doeth a whore

That would men’s fanatasies allure.

Paint not thy face in any wise

But make thy manners for to shine

And thou shalt please all such men’s eyes

As do to Godliness incline.

Bishop Nicholas Ridley saw the potential in both Crowley and Fox…….

…….and ordained them deacons. But King Edward died at the age of fifteen, his half-sister Mary Tudor ascended the throne……..

………and England became Roman Catholic again.

And again a dangerous place for Crowley and Foxe. Both men fled to Europe – with Foxe and his pregnant wife narrowly escaping arrest. By 1555 they were both in Frankfurt – the year Bishop Ridley suffered a slow and agonising death at the stake…..

During this, Foxe later reported, Ridley continually cried out:

Let the fire come unto me. I cannot burn.

Foxe had already started to chronicle the lives and deaths of historical Protestant martyrs – but now he undertook to cover present-day martyrs as well. In a very modern way, he started to interview all those people who had witnessed their deaths.

It became his obsession, so all-consuming it finally killed him.

Crowley and Foxe now so hated the Pope – whom they denounced as ‘Satan’ and ‘The Antichrist’ – and all the ‘Romish rags’ of his ceremonials, they even refused to wear surplices.

Queen Mary died in 1558. Queen Elizabeth ascended the throne………

….. and England was Protestant again. Crowley and Foxe were heroes.

Crowley returned to England the following year with a new wife – and was immediately given a church sinecure. He gave up printing as he realised that he could reach more people by preaching.

Foxe was also given a sinecure which allowed him to write the first English version of his martyrology, printed in1563. It went on to become, after the Bible, the most popular book in English.

In his Epigrams Crowley had attacked Priests who held more than one office. By 1565 he held five – the last of which was Vicar of St. Giles’. But Foxe and Crowley really did practice what they preached. They gave all their own money to the poor – so much so that Crowley’s widow was left destitute and had to be bailed out by a pension from the Stationers’ Company.

But there was a problem. Queen Elizabeth, a mass of contradictions, had been brought up as a Calvinist – but was aesthetically attracted to Rome. She had lit candles on her private altar and celebrated the Mass in Latin months after it was illegal to do so.

She demanded her priests to wear copes and vestments.

Crowley confronted Archbishop Parker about this…..

….and accused the Queen of ‘caprice’. He insisted he would never wear ‘the conjuring garments of popery’. The following year, 1566, he entered St. Giles’ to find a funeral service being conducted with all the lay clerks wearing surplices.

What followed was described euphemistically as ‘a tumult’ – but it was a punch up so severe it led to Crowley’s imprisonment and dismissal.

Foxe unofficially took over the running of St. Giles’s for the next twelve years. He moved into Grub Street – now Milton Street – just round the corner from the Church and lived there, in the parish, till his death.

In 1571 Sir Thomas Lucy became the M.P. for Warwickshire which entailed attendances at Parliament in Westminster – and where better to worship than St. Giles’ where his old boyhood tutor, Foxe, was taking the services.

We know it later became a Lucy family church because his great granddaughter, Margaret, was buried here – and has a memorial.

Crowley softened in retirement – especially when the Pope issued his 1570 Bull which ordered Catholics to disobey Queen Elizabeth. He became fiercely patriotic and even agreed to wear vestments to please the Queen. He was forgiven and re-instated as the Vicar of St. Giles in 1578.

So when Lucy visited London again in 1584, Crowley was in situ but his old tutor was living round the corner.

Shakespeare by then had been in London for a couple of years – on the run from Lucy. What more natural than to seek help from the two priests who not only knew Lucy but were writers as well – one of them a celebrity.

And what more natural than for the priests to intercede with Lucy – and then to ask for something back from Shakespeare in return. My belief is that Crowley and Foxe got Shakespeare to write Biblical Plays and Morality plays – like ‘The Fair Em’ – and tour the Midlands with them.

But what evidence do we have? Again, the coded attacks of the University Wits. Greene’s famous ‘Upstart Crow’ attack on Shakespeare also has a passage which is rarely quoted in which ‘Roberto’ – Greene – confronts ‘The Player’ – Shakespeare.

‘Roberto’ says:

I took you rather for a Gentleman of great living, for if by outward habit men should be censured, I tell you, you would be taken for a substantial man.’

So am I where I dwell (quoth the player) reputed able at my proper cost to build a Windmill. The world once went hard with me, when I was fain to carry my playing fardle on footback; but it is otherwise now; for my very share in playing apparel will not be sold for two hundred pounds.

Truly (said Roberto) ‘tis strange that you should so prosper in that vain practice for that it seems to me your voice is nothing gracious. Nay then, said the Player, I mislike your judgement: why I am as famous for Delphrigus and the King of Fairies, as ever was any of my time. The twelve labours of Hercules have I terribly thundered on the stage, and played three scenes of the Devil on the High Way to Heaven. Have ye so? (said Roberto) then I pray you pardon me. Nay more (quoth the Player) I can serve to make a pretty speech, for I was a country Author, passing at a Moral, for ‘twas I that penned the Moral of Man’s Wit, the Dialogue of Dives, and for seven years space was absolute interpreter to the puppets. But now my almanac is out of date:

‘The people make no estimation

Of moral’s teaching education’.

After seven years, it seems, the public had tired of morally uplifting plays.

Simpson believes there is also a scurrilous satire on Shakespeare’s touring days in the play called ‘Histrio Mastix’ – which he thinks was originally written by another University Wit, George Peele.

Shakespeare becomes an actor called ‘Posthaste’ who leads a tiny troop of would-be actors – and whose artistic inspiration springs directly from alcohol. He and his actors cannot give any money to the poor because they are so poor themselves – and are entirely dependent on ‘the merry knight, Sir Oliver Owlet’ – a satire on Lord Strange – and their ‘ingles’ – their rich gay lovers – brewers and hobby horse makers – who are constantly ‘troubling’ rehearsals.

The company finally collapses with the threat of the Armada. People regard actors as skiving and unpatriotic – and soldiers seize the costumes of the actors for the ‘real men’ who are fighting the Spaniards. Postehaste says he has ‘no stomach for these wars’ – and resolves to ‘boldly fall to ballading again’.

There’s a member of the St. Giles’ congregation who would have despised this attitude of Postehaste’s – Martin Frobisher……

……..who led one of the four squadrons against the Armada – and is also buried in the church.

How much of Peele’s satire is true, we shall never know. But we do know that Foxe died in April 1587 and Crowley in June 1588 – Armada year.

And in November1589 Shakespeare’s touring career was brought to an abrupt end. Lord Burghley – Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary of State – had requested that the Lord Mayor stop all plays being performed in London. The Lord Mayor said he could answer for only two companies – the Lord Admiral’s and Lord Strange’s.

The Lord Admiral’s Men had obeyed him but ‘the latter parted from him in a very contemptuous manner’ – and went and played at Cross Keys that very afternoon: ‘whereupon he had admitted two to the Counter’.

The Counter was a prison – and ‘contemptuous manner’ sounds very like Shakespeare…..

Nashe’s nick-name for him was ‘Caesar’!

So how did Shakespeare – in the ‘Upstart Crow’ attack – end up possessing theatre costumes worth £200?

Was the Catholic network at work again?

Nicholas Rowe certainly suggests it was. He says – again with evidence from William Davenant – that the Roman Catholic Third Earl of Southampton……

……..gave Shakespeare the gift of £1,000. And all the indications are that by 1590 Shakespeare was in the pay of the Southampton family.

He wrote seventeen sonnets to celebrate the Third Earl’s seventeenth birthday. In these sonnets he plays on the family motto – ‘Ung par tout’ – ‘All for One’ – and praises the Earl’s dead father and beautiful, widowed mother, the Second Countess, Mary.

Mary was an ardent Roman Catholic – and even sheltered Jesuit Priests in her London home in Holborn. The Jesuit Robert Southwell………

……was thought to be the Third Earl’s confessor. He was also a poet and the ‘burning babe’ imagery he uses in his work is thought to have influenced the ‘naked, new-born babe’ image Shakespeare uses in ‘Macbeth’.

Shakespeare was also influenced by Robert Persons way before the Oldcastle scandal. Persons wrote the ironically titled ‘Leicester’s Commonwealth’ – an attack on the Earl of Leicester – comparing him, among other villains, to King Richard III.

Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’ can be read as a satire on the Queen’s favourite.

Both men pose as holy men – and both murder and seduce their way to the top.

Shakespeare also makes an unconscious slip in an early printings of the of the play when he names King Richard ‘the Bear’…….

But the Bear and Ragged Staff was Leicester’s symbol . He should have written ‘the Boar’ which was King Richard III’s symbol.

He changed ‘bear’ to ‘boar’ in subsequent editions of the play.

Also Shakespeare’s only purchase of land in London, in 1613, was Blackfriars’ Gate – a notorious recusant hideaway, famous for its secret passages down to the Thames, priest holes and Latin Masses.

So Shakespeare had soon thrown off the influence of Crowley and Foxe.

But had he? There remains a bizarre Puritan streak in Shakespeare’s writing right to the end.

Hamlet attacks Ophelia for wearing make-up:

I have heard of your paintings too, well enough: God hath given you one face, and you make yourselves another.

And King Lear – in his great prayer on the heath – calls for the voluntary redistribution of wealth:

Take physic, Pomp, expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou must shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

Of course, you could say these were the thoughts of characters in his plays – not Shakespeare’s own thoughts. But we can find Puritan ideas in his private sonnets as well.

They reveal Shakespeare hates make up. He hates the use of wigs. He hates artifice in writing. He hates artifice in speaking. He hates promiscuity. He hates lust. He hates, at times, the whole of greedy, power-driven, frivolous, Elizabethan society.

And his great sonnet 146 is actually a Puritan prayer. Shakespeare addresses his own soul and describes his body as his ‘sinful earth’. ‘Rebel powers’- his physical appetites – persuade his soul to dress his body in fine clothes and give him food and drink in excess.

He is like a man who paints the walls of his house in a flashy way to give the appearance of being rich while he is, in reality, drooping with hunger and want.

Shakespeare resolves to…

…..feed on death, that feeds on men,

And death once dead, there’s no more dying then.

Did Shakespeare follow this ascetic path? A glance at his monumental bust in Stratford Parish Church would suggest not.

Indeed there are anecdotes of his passing out during drinking bouts at Stratford – and the Stratford vicar, John Ward, reported in 1663 that he died after a ‘merry meeting’ with Ben Jonson and Michael Drayton.

And for every Puritan Sonnet you can find a Roman Catholic – or even a pagan one. Shakespeare employs images and phrases from Catholic church ceremonial – and even scripture – to celebrate his love for the Earl of Southampton. And at the end of the day he, like Ovid, is far more interested in the immortality of his verse than of his soul.

Shakespeare wandered furthest away from the teachings of Crowley at the end of his short life. He mixed with rich crooks and villains at the Bear tavern in Stratford – the Combe family and a man called Replingham who planned to do what Crowley hated most: enclose the land.

This meant that the poor would lose common pasture and fuel for their fires. Replingham would farm sheep which, according to Sir Thomas More, ‘eat up, and swallow down the very men themselves’.

The whole Puritan council of Stratford was against the enclosures – and wrote to Shakespeare for his support. Shakespeare stood to lose money as he had bought outright a share of the parish tithes – again a practice Cowley deplored.

The loss of peoples’ incomes would affect Shakespeare’s own pocket.

But instead of siding with the Council, Shakespeare came to an understanding with Replingham. He would be compensated for any loss. Shakespeare drafted the contract himself in his own hand.

He – and his son-in-law, the Puritan doctor John Hall – kept insisting the enclosures would never happen. But they did. There were fist fights between the Councillors and Replingham’s thugs – and by night the women and children of Stratford – including, it seems, Shakespeare’s own daughter Judith – would fill in the holes Replingham’s men had dug.

But Shakespeare did nothing – and this so shocked the playwright Edward Bond……

………he wrote his play ‘Bingo’ as a response. He had assumed Shakespeare would be as Socialist as he was.

But what Bond didn’t know about was a diary entry for September, 1615 by Thomas Greene – the Stratford Town Clerk and a relative of Shakespeare. He records how Shakespeare confessed to Greene’s brother, John, that:

he was not able to bear the enclosing of Welcombe.

Shakespeare died a few months later and the enclosures stopped. Whether he did anything to bring this about we may never know.

But I like to think he finally acted on the ‘common wealth’ principles he had heard Crowley preach, all those years ago, in this beautiful church.

Thank you Stewart for that amazingly erudite and informative essay on Shakespeare’s connection to the Church of St Giles.

Your work is as always superbly researched and illustrated with the relevant portraits.

In appreciation

Rosemary

Dear Rosemary, I cannot thank you enough for your comment! God bless.

So sorry to have missed your talk 2 Sundays ago. Having read it through it looks really interesting and very well put together. This morning before Mass, Father Jack told David how engaging your presentation had been!

Margaret Preston